Challenges on the way towards a common ground of body psychotherapy – Body psychotherapy versus the established areas of psychology.

by Lennart Ollars

I believe that we need to move towards a common ground of body psychotherapy, and also that we need to enter into a more professional dialogue with the world of established and academic psychologists. These are no easy challenges. I will address some of the difficulties I see as connected to these processes including what I perceive as our fears and resistances. And I will suggest a few steps in both (interconnected) directions: what is the common ground of body psychotherapy and how can we establish a dialogue with the world of academic psychologists?

Some of the difficulties, I believe, reflect that we are living in a conflict field.

On the one hand, there is the field of conflict between different psychological and also psychotherapeutic approaches and traditions; basically a conflict that is much broader than just between body psychotherapists; a field of competition and a striving for recognition that is going on between different ways of thinking and working within psychology in general. This field also includes a fight among scientists and among different scientific traditions.

On the other hand, there is a more personal and relational field of differences, animosities and polarities between people, a conflict field that has to do with a complex mixture of emotional, personal and cognitive stuff.

Nevertheless, both areas are important, as well to some degree for our personal future, as certainly for the future of body psychotherapy.

I will give you my personal background and motivation for being preoccupied with these questions. I am originally educated as a psychologist, and also as a relaxation therapist. After working with youngsters and families for 4-5 years in a regular job as a clinical psychologist, I spent most of my time in the next 15 years as a senior trainer in the Bodynamic Institute, developing and training Bodynamic Analysis, which meant working in a private institute, without much contact with the academic world.

In the last 4-5 years, I have picked up my contact with my original professional subculture, for several reasons, among which are both a wish for new personal challenges and also a strong motivation to get body psychotherapy more recognized within the professional establishment.

Today I function as a part time professor at the Psychological Institute at the University in Arhus, Denmark (my seminars are titled: Body Sensation, Personality Development and Psychotherapy), and as a part time free lance psychotherapist, supervisor and teacher, mostly in body psychotherapy. Among other activities I am also a member of the Psychotherapy Committee in the Danish Psychologists Association. I still work as a guest teacher for Bodynamic International, an Institute with a way of working I feel strongly connected and associated with.

So I am certainly trying to dance with both worlds; the established and academically rooted psychology world on one side and the body psychotherapeutic subculture on the other side. On my good days, it feels like a meaningful challenge to get both worlds to learn from each other.

What is preventing us from formulating the common ground of body psychotherapy? When you hear me listing all the difficulties and resistances (we are vulnerable, we have a hard time to enter grown up dialogues, we suffer from mixed relations, etc.) you might think that I believe that body psychotherapists are especially sensitive and vulnerable, and more so than other professionals, but this is not the case.

If we look at the ground and history of psychotherapy in general we will see the same pattern: most people (authors, trainers, professors and scientists) are more preoccupied with stating their own way, than with entering a dialogue with other ways of working. They suffer from the same resistances, unwillingness to look at conflicts and competition as we do. At least that is my impression from encounters with other professionals in the area of psychotherapy and psychology in general; not the least within the academic world. Universities and associations of psychologists are pretty cold, competitive and are tricky relationship subcultures to encounter. Certainly, you meet people you like and feel connected to, but the level of distrust and manipulation is high. So, there is no need to be ashamed, or to try to hide away our sore spots: let’s rather face them with our heads raised. If we dare to do that, we are already doing much better than most other professional subcultures. Wouldn’t it be nice if other professionals, in EAP or in the academic world, a few years ahead were talking about body psychotherapists like this. “Hey they might be a bit special, but they actually dare to talk about the real difficult stuff.”

So let’s look at some of the problem issues.

We have been busy finding and describing our own way of doing things, so we haven’t been ready to find a common ground.

It’s pretty hard to find out who you are yourself! Or, essentially the same point: we spend our time doing our own stuff, and can hardly find time to describe that way, so there is no occasion or energy left to discuss. I know that this is true for myself and my close colleagues, and I believe it is also a good description of what energy has been spent on in other body psychotherapist networks. Maybe we had to do this; maybe any psychotherapist has to do this for some years before he is really ready for a critical dialogue. Are we ready now?

Establishing EABP was in itself a step in the right direction, as it set a platform. But how do we use the platform?

We do meet, and we do present what we are doing, and we do write papers. But are we also ready to discuss and criticize each other? Without getting totally hurt and offended? Are we ready to share these hurt and offended feelings? Are we open to criticism from colleagues from other traditions, and from former trainees or do we tend to become defensive, dogmatic and imperialistic?

I believe that we have to start with sharing some of our resistances. If I were to be honest, I must admit that I know all the feelings and reactions just mentioned. The following headlines could be clues to why we have all these resistances.

Threats against our inner truth.

What I do is me, other ways threaten my inner truth. Doing body psychotherapy is maybe an even more personal matter than doing verbal psychotherapy, so discussing the way to do it is like discussing your own very core or existence. Are we willing to expose our way of working, that is to expose ourselves to each other? And listen to critical questions? I know from experience that this is not easy. But imagine that this is OK; imagine that nobody has to be perfect. If Irvin Yalom can even write books about his doubts and blunders, why shouldn’t we? Let’s admit that it hurts when we offend each other, but let’s try to stay in contact anyway. Let’s share some blunders and mistakes. We have been doing ‘sharing blunders’ among my close colleagues, and it has been a relieving experience. And we continually hurt each other from time to time, by not hearing, misunderstanding and misinterpreting. The only recipe to heal this we have found is admitting the pain, and to stay in process and dialogue, or at least to come back to process as soon as possible after ‘licking your wounds’. Eventually get help from a mediator.

Our weakness is to be stuck in ‘early’ contact patterns.

I have an analysis to share, based on many experiences, including looking into my own reactions; I believe that many of us, including myself, sometimes get stuck in ‘early’ contact patterns. Psychotherapists in general, and body psychotherapists in particular are much better at building up sensing yourself and your core and often also improving contact to the close other than in developing a self-observant ego and other group and discussion abilities. Are we willing to learn about boundaries, and to start talking about our differences and to stay in contact learning to dialogue and solve or just handle polarities?

One of the basic antidotes against getting stuck in early contact patterns is this: tell yourself that the person who is offending you or not hearing you, is actually not your mother or father forty years or more ago, but just a Danish clumsy guy. Or, the guy who misunderstands you is not a Guru-like world expert in body psychotherapy, but just a trainer with a headache, or his mind somewhere else. I am willing to admit that it is not always easy, but try it. If this doesn’t work, there is only one way left: share it, and have somebody around, preferably the one you have a process with. It’s basically the same quest: do we trust ourselves and each other enough to dare to disagree, to question each other, and to stay with differences and disagreements, coming from the past or taking place just now.

Frankness concerning strengths and weaknesses.

If you are an Audi-salesman, you most likely do not discuss the advantages of Mercedes. Most of us need to have new clients coming around, or need to get our training’s filled up with trainees, so we spend our time promoting ourselves. Looking at other ways of working, especially if they are pretty close to your own way, is threatening and a bit like appreciating your competitors (or maybe even enemies?). Are we willing to look at, and to discuss what others are doing differently, and maybe even better than ourselves? We have to enter discussions like this, if we really want to form a common ground for body psychotherapy, and if we want to proceed in the direction of mature and critical dialogue, in order to develop our understanding and way of working further. And we certainly need to share questions like, what are not only the advantages, but also the weaknesses connected to our own way of working? No modality of psychotherapy has all the answers, not even body psychotherapy. No sub modality of body psychotherapy covers everything, maybe not even Bodynamics!

I will share a couple of good learning experiences with you. Approximately 14 years ago I participated in one of David Boadella’s training groups. One evening I challenged David on the fact that he almost never worked with relationships, or the relational field, but concentrated more on subtle integrative body-stuff. I saw a weakness there, and I wanted him to improve. I was expecting (and honestly maybe even looking forward to) some kind of verbal combat, but to my surprise his answer was totally non-defensive, “You are right, I am not especially good at that, it doesn’t really attract me or amuse me, you yourself are much better doing that, but couldn’t that be OK?” Oups! As you can guess I did not learn much about relationships at that training, except from this encounter, but I learnt a lot of other nice things. Among those was respect for a teacher who knew (at least one of) his weaknesses.

About two years ago, I had a client who was very obviously suffering from at least one, probably several heavy shock traumas. Part of this story is that I already then considered myself to be a pretty skilled therapist in handling shock trauma, so I presented her to ‘the whole package’ of my bodily-oriented Bodynamic methods, with lots of confidence and certainty. I was presenting something I was pretty sure of, something I had even written papers about and presented with reasonable success on one of the EABP conferences. To my big surprise she quite quickly and completely unimpressed stated, “No thanks, I don’t want to do that, it doesn’t sound like something for me!” I could have dismissed the client, maybe I would even do that with other clients, just saying goodbye with mutual respect, “We don’t fit together, bye, bye.” In this case I chose to stay though, and to do things she wanted that were completely ‘out of the book’ compared to what I usually do. So, getting back to track. I believe that we have to develop our consciousness of preconditions and limits, weaknesses and strengths of all methods, and openness to what fits the individual client. One big part of this is to be willing to look at strengths and weaknesses in our own tradition or modality of body psychotherapy, compared to other modalities. I suggest this as an informal theme for night-discussions for this congress.

Learning to face and handle mixed relationships.

I know from personal experience, both as client, trainee, trainer and educational manager that mixed relationships do not per definition provide open and mature discussions of theory and methods. Our collegial field is more than filled up with mixed relationships, so the question of looking at similarities and differences is polluted with personal issues. It’s not easy to ask critical questions to your former therapist or your former trainer. And it is not easy to separate the personal feelings from the factual content in a debate. It’s certainly not easy to challenge and maybe criticize someone 15 years after he might have hurt you personally in a training group, if this incident has never been processed to a resolution or a mutual containment.

Are we willing to learn about boundaries, mutual respect across personal pain and relationship difficulties and to stay in contact learning to dialogue and solve or just handle polarities and conflict, instead of cutting off and leaving? I believe that we have to step very carefully into this field, that is to do it slowly and with respect for the other’s readiness, but I am also sure that we have to admit openly that it is there, and to try to first acknowledge and then separate personal disappointments and other painful stuff from discussing topics of theory and working methods. We should try to avoid what I recently heard Malcolm Brown call ‘character-assassinations’, or using our theory to ‘analyze assassinate’ others instead of listening and answering on the level of verbal content. Even though individuals certainly most often do speak from their character-defenses, especially in emotionally loaded situations. Good luck to all of us, on this one! The first step is to admit that mixed relationships have been, and still are difficult – and to share experiences of this on a concrete level.

What can we do with all this resistance – these difficulties?

All this might sound pessimistic. But actually, it is my gut feeling that we are pretty ready to take the next steps to enter a more frank and straightforward dialogue.

One place where I have experienced some of this readiness is in the FORUM of the EABP. The mutual visiting and assessment of each other’s process and the subsequent dialogues are an opening, even though it can hurt too. I hope this process will continue in the FORUM, and I hope that all traditions will join this FORUM – the dialogue in there is really an opportunity to learn to hear and understand better, and maybe respect even those you initially believe are far out seen from your own point of view.

Another platform is offered to us at the congresses. Especially this congress, with conflicts within systems, and between systems as a theme. Hopefully some of the presentations and panels will help us along. Personally, I believe that the most substantial processes can take place in the breaks, and at night – if we dare to follow up on the congress themes on a more informal and personal level. An idea for the future congresses could be presentations followed by critical panels. A model we have been using in Bodynamic Trainings with good results.

Describing what you actually do as a psychotherapist is pretty difficult.

There is one more difficulty we have to encounter, if we want to start formulating the common ground of body psychotherapy, and to start looking into our differences. It is actually much more difficult to describe what you are doing as a psychotherapist than just doing it, and this task is probably even more complicated when you also work with subtle bodily processes.

As this difficulty is of another kind than the other themes I have mentioned, being more a question of how to do it than a question of personal resistance, I will save this one for later.

A few steps in the direction of a common ground of body psychotherapy.

I believe we have to start with the obvious and simple, so I will dare to do that, with the risk that I am called superficial. I will suggest a few models that might be some of the bricks in building a common platform or common ground of body psychotherapy

Let’s presume that we agree on one simple statement, formulated by Wilhelm Reich, “We all understand the human being and development as a functionally psycho-socio-physical entity. Bodily, psychological and social aspects of man are interconnected and can only be fully understood in this context. ” One first rather universal model to illustrate this could be The Jukebox Model.

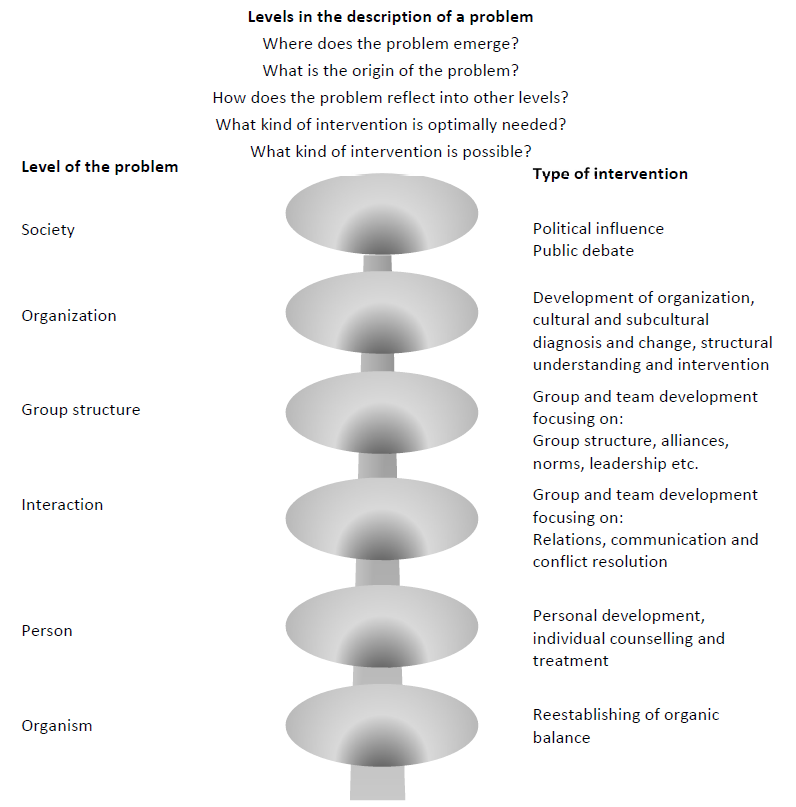

The Jukebox Model

The Jukebox Model or ‘Levels in the Description of a Problem’, is a model developed by myself in cooperation with the Bodynamic network. The model certainly is inspired by the work of others. The essential idea of the model was given by two senior psychologists in Denmark some 18 years ago, Kurt Palsvig and Gunnar Hjelholt. They in their turn had picked up the idea from Erich Jansch.

My own contributions to the model as it looks now are adding ‘the organism disc’, the graphics, and finally using it consequently as a helping/searching tool in psychotherapy as well as supervision (Ollars 1996). The main idea is that different ‘layers’ of human life are connected, and in some sense connected to and reflected in each other. Nevertheless working on the different ‘layers’ requires very different tools and skills.

Finally and functionally essential, it is very recommendable firstly to be aware of how ‘the problem in question’ is connected to or reflected in each ‘layer’ and, just as important, secondly on which ‘layer’, with what kind of understanding and intervention you choose to approach ‘the problem in question’.

This is why the model is called ‘The Jukebox’; it helps you to overview possible choices, and when this is done you choose the disc you prefer to use at that very moment. See the graphic above.

One way to use the model is to understand how different psychotherapeutic approaches provide specialized approaches on different levels. Clearly family therapy primarily approaches the group dynamic level and the relationship level. Gestalt therapy is pretty good at working with relationships, and also concerned with what happens in the body, seen from a communication and ‘finishing of gestalts’ point of view, although not so elaborate at the body level as body psychotherapy. Body psychotherapy in general is of course very aware of what happens on the body level, and from there…

Maybe this model could also help us distinguish between different sub modalities of body psychotherapy. I will pick up this last point later. Now to another model; the ego aspect-model from Bodynamics.

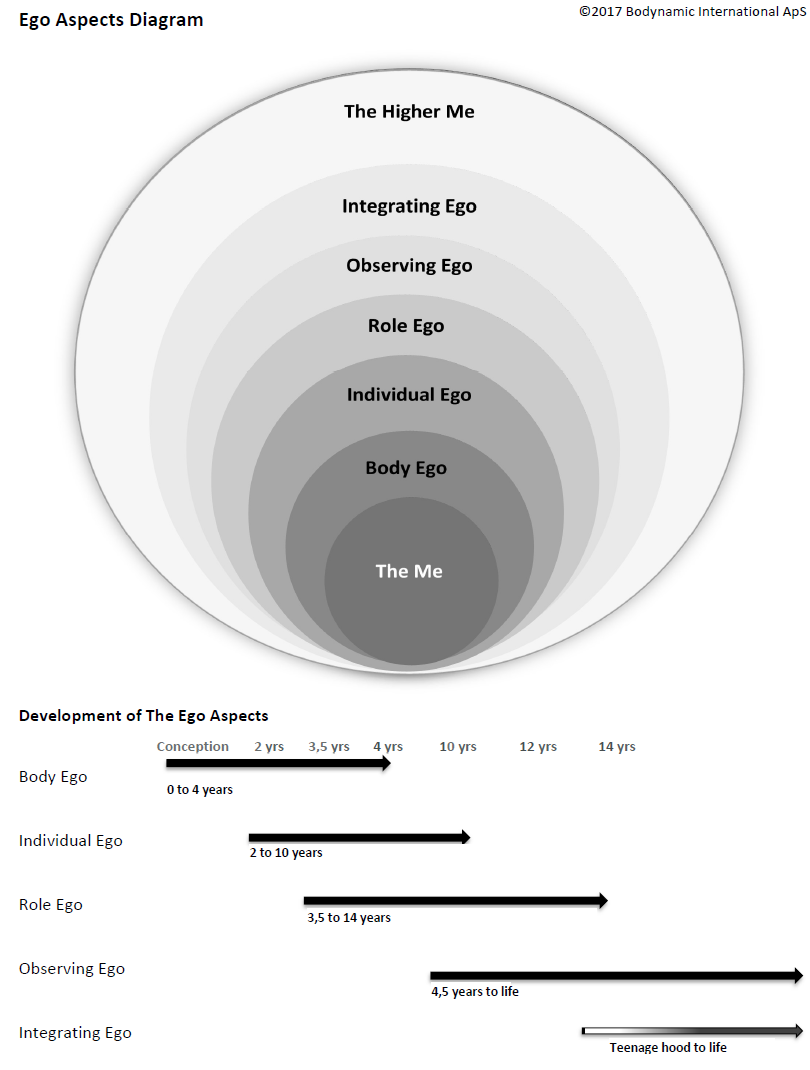

The Bodynamic Ego-Aspect Model

This model I would like to present as a possible brick in building the common platform for body psychotherapy. It was primarily developed by Lisbeth Marcher, as usual in our tradition in close corporation with the colleague network in Bodynamics. Lisbeth Marcher and myself presented the model at the EABP Travemunde Congress two years ago, (1999).

The model reflects the experience that ego and ego development has to do with a lot of different processes, connected to different aspects of the human being and development. In a way, it could be seen as a direct graphic illustration of Reich’s “functional entity of bodily, psychological and social aspects of man”. Like, as it was the case with the jukebox model, one of the intentions of the model is to help establish some mental overview and order in phenomena. Look at the model now, below.

I’ll give a short explanation of the model.

Ego formation includes from the very beginning a lot of preverbal, bodily processes as described a long time ago by Jean Piaget or recently by Daniel Stern. These processes are in a way also cognitive and emotional, but mostly rooted in bodily processes. They certainly are preconditions for development of the next layer, individuality, or psychological experience of individuation, my ego, me. This layer is connected to boundaries and content of the individual ego. How man experiences himself as himself, from the inside. The third layer has to do with formation of roles, the different ways we develop to interact with other people in different social contexts. The fourth layer has to do with development of the ability to observe and reflect on one self, an ability that according to most developmental psychology is beginning to unfold from the age of approximately 1 1/2-2 years. Later layers are somewhat but not totally dependent on the development of earlier layers.

Around these four circles we have the social structures and sub cultural schemes in which all this is developed. Nothing from the developing of the fetus to handling teenage development can be fully understood unless we are aware of where, at what time, what subculture, what culture and structure of society, etc. I wonder how many body psychotherapists would agree with this basic model? If one chooses to relate the psycho therapeutic work to ego development, it might be necessary to develop a more elaborate model of body development and ego development or developmental psychology, like the character-development-model in Bodynamic Analysis. This would go beyond the common ground I believe, and into one of the possible sub modalities of body psychotherapy, so in this context I will not follow that path.

Now to a next model, which is a task-oriented model of body and mind developed by one of my Danish friends, Soren Willert.

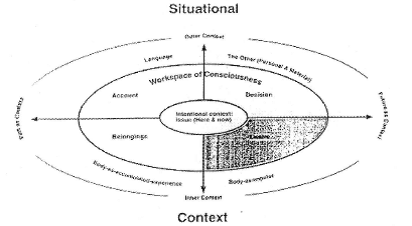

The Function of Consciousness

This model is developed from an urge to know where to go, when you sit in front of a client – person or organization so therefore it is very oriented towards practice, focusing on what is going on in the consciousness of the client (and the therapist). Soren Willert, a Danish psychologist and a senior professor in psychology at The University of Arhus developed the model over the last 10 years. The model is based on the thoughts of the American pragmatist-philosopher-social psychologist George Herbert Mead (Mind, Seit & Society, 1934), and inspired by B. J. Baars’ Global Workspace Metaphor. The model was presented internationally at the Tucson Conference Toward a Science of Consciousness in April 2000. I suggest that you have a look at the model below.

The model describes the workspace of human consciousness. Imagine the consciousness as a helicopter. In the center, we find the intentional context: ‘The Issue’, what is in focus here and now. The consciousness can potentially travel around in the workspace, and focus on or pick up what happens there. The potential workspace is characterized by two polarity dimensions: inside – outside, and past – future. Inside-oriented is what potentially can be picked up from the body: impulses (desire) or structural, you might as a body psychotherapist say tension patterns or bodily reflections of experience (belongings), outside-oriented is either what we call stuff, our concepts and conceptual framework, very much formed through language (the account or the narrative story) or preparations and processes on the way to act or interact, very much directed towards the other in a broad sense (decision).

The Function of Consciousness: Biological, Psychological and Organizational Perspectives

What I like very much about this model is that it explicitly puts the body on the map. No full understanding of consciousness without an understanding of bodily as well as outer context. Man, is both body, thought and action in his environment. Man’s consciousness can focus more or less on all this.

It almost sounds like Pierre Janet: “There is nothing in consciousness but action and the derivatives of action” (quoted from Boadella, 1997). In this case though the model is developed by a contemporary, academically well rooted psychologist, who is certainly interested in connections between body and psyche, but not especially committed to body psychotherapeutic thinking. The model also implicitly points out that whether you are specifically interested in acting (behavioral approach), in the accounts or concepts of man (cognitive or narrative approach), in the past (psychodynamic or psychoanalytic approach) or the future (approaches based on learning theory or logo therapeutic thinking) it is all connected. And the body is always a part of what is going on. Finally, I like the model very much as a practical searching model, a tool that can help you from moment to moment as you work with counseling, supervision, or psychotherapy.

What are the difficulties in opening a dialogue with the established and academic psychology world?

My first point concerning what prevents us from starting a dialogue with the field of established and academic psychology was the obvious one: it eats energy to discuss with others than your close ones, especially if you want to write or even conduct some kind of scientific exercise. Can anything be done to help us survive this?

Quoting my grandmother, “United we stand!”

I am realistic enough to realize that writing, discussing, going to congresses, inviting other professionals to dialogue and initiating even smaller and non-pretentious pieces of scientific validation really takes time and so to say, ‘eats energy’.

This fact we cannot change. We can hope that a certain number of us hang on. And maybe we could get better in helping each other. This is where my grandmother comes in: whenever we had to part, she often said, “United we stand!” Like a kind of mantra, let’s remind each other that you can rely on me and I can rely on you!

The only way to ease the perspective of ‘lots of hard work ahead’ that I can see is that we find ways to support each other in this work – more cooperation. Maybe solving certain tasks together. Less ego-tripping. No easy task as I have mentioned earlier. But a necessary one. A practical suggestion could be to leave 5-1O % of the EABP income to finance mutual writing and documenting projects (alas I know we have no money). Another idea is to find someone who can support us in fund-raising, to apply for money somewhere. Important tasks for example for the new EABP Board and for the FORUM of the EABP. As mentioned I believe that a next set of difficulties has to do with fears: fear of losing your own or our special way of working, maybe fear of becoming too established, probably other fears of a more personal kind, related very much to the resistances I have already addressed above, and probably a crucial one is the fear of discussing with academics, because they know much more than I do! I will address the last of these fears.

Swallow fear and feelings of inferiority, because there is no actual reason to have them, and start talking and asking.

It’s true enough that people who are academically trained sometimes know and use a lot of words, and this is not only meant sarcastically. If you are trained for example as a psychologist you know (or at least did know) a lot of different theories, and you are more or less trained in critical thinking.

But in my experience, when it comes to the more operational knowledge and skills in handling communication and solving problems, including understanding what are the finer dynamics in the psychotherapeutic session, academics are not wiser than non-academics. Some even have the handicap that they are more (too much) focused in the head, and less trained in sensing themselves. Traditionally in most countries I have heard about, academic training to become a psychologist contains much less practical contact training than we as body-psychotherapists are used to in our trainings.

So, relax, they might know a lot of words, but they are not that clever, so start asking questions and start telling what you do and think yourself!

The basic, common, shared, more or less scientifically validated knowledge about psychotherapy.

Somebody might think that more academically accepted psychotherapy traditions have more well described and specific knowledge about what works in psychotherapy. This is not the case.

The recent 30-40 years’ exploration into the outcome effect of different ways of working in psychotherapy has the following results, roughly speaking. It is proven that psychotherapy works, it is helpful for approximately 80% of clients.

Why it works is not quite clear. In a scientific sense the finer dynamics are not yet validated. Research also shows that there is no significant or substantial effect connected to the way the therapist works. No method or tradition seems to be better than others, as far as research up till now is concerned. The factors that have most importance for a good effect of psychotherapy appear to be that 45-50% of the effect of psychotherapy seems to be dependent on factors that have to do with the client. And approximately 40% of the effect has to do with factors connected to the therapist as a person, and to the quality of the contact between therapist and client (the so called non-specific factors). This leaves 10-15% of the effect probably ’caused’ by different techniques, or ways of working (Asay and Lambert 1999).

Now certainly these results and their preconditions are open to discussion, but nevertheless they are interesting, and shared with a reasonably big consensus among academically founded psychotherapists. The overall, and also commonly shared conclusion is that we don’t know very much about what the dynamics actually are behind the non-specific factors, or in other words: what actually goes on between therapist and client when therapy works well, and when it fails or works less.

So we ought to research more into this area! These figures might be known by many of you, but I have chosen to mention them anyway, because they are good to remember when you discuss with therapists from traditions other than your own, including academically trained therapists. This is my point. Relax, because nobody really knows very much

We must relate what we are doing to some kind of psychological model or theory!

If we want to talk to other therapists, including those from the more established and academic world of psychotherapy and psychology we have to use at least some of the common language. In other words, it’s necessary to relate what we are doing to some kind of psychological personality models, or interaction models that are used. In a broader professional context than just our own. It’s obvious seen from a communication point of view, that knowing at least some of the native language is helpful if you want to be heard. At the same time it is a good learning experience to try to relate to our own, sometimes very locally developed language, and some of our non-spoken knowledge to commonly used language within connected areas: psychotherapy and psychology.

This thought leads me directly to a more tricky point, namely the simple question: what is it we are actually doing?

Are we based in some kind of psychology, or are we merely skilled masseurs clever in following energetic processes?

I believe that it is pretty crucial that we become aware and more outspoken concerning our differences, and possible weaknesses or problems:

- To what degree do we work within a regular psychotherapeutic framework?

- To what degree do we explicitly relate our work to a psychological model or theory?

- Are we based in some kind of psychology, or are we merely skilled masseurs clever in following energetic processes?

So with the risk of offending some of you, because I see this exercise as necessary for our mutual survival, I come now with an important question. How does the therapist work with the client or group – mostly nonverbally, verbally or in a combination? Another way to state this point could be to question whether what happens between client and therapist can actually be accurately described as a modality of psychotherapy, or should rather be described as a form of bodywork, movement therapy or massage – all these ways of working that are more familiar in physiotherapy, relaxation therapy, Rolfing or other ways which improve well-being or inspire personal development rather that they are psychotherapy.

Let me give an example: A good Rolfing session is wonderful, and might very well be an important part of a personal developmental process, but it is not psychotherapy. Bodily oriented ways of working have been used, and are used, as well within a psychotherapeutic context as within several non-psychotherapeutic contexts. This fact is as I see it an important reason for the sub modalities of body psychotherapy to declare themselves (and to document that they are intact) psychotherapies and not merely bodily oriented techniques of providing well-being and development.

Whether a way of working with individuals or groups with good reason can describe itself as a kind of psychotherapy depends on a series of questions, of which, by the way, there is also no common shared consensus.

I would suggest questions like:

- Is some kind of clarified understanding of personality and personal development used as a basis for the way of working in question?

- Are enquiry, problem recognition and problem analysis and a working contract clearly stated between client and therapist and part of the way of working in question? If so, is this working contract regularly followed up with a mutual evaluation of the outcome of therapy?

- Is the relationship between client and therapist, including an awareness of transference and counter transference (or these phenomena described in other words) recognized and part of the teaching and the way of working in question?

Answers to questions like these would be helpful to clarify whether the way of working in question could be considered as a form of psychotherapy, although not necessarily helpful in clarifying whether the same way of working is scientifically validated.

I imagine that this crucial point is the main reason why the EAP wants the different sub modalities of body psychotherapy to make the so-called scientific validation. But, what is more important, if we are not clear about what we are doing, and ready to experience and describe ourselves as psychotherapists, we are surely to get difficulties in getting recognition within the established and academically founded universe of psychotherapy. My last point under this heading has to do with the numbness, tiredness and breathlessness that many people experience when they hear the words: science, scientific, scientific validation, etc.

On the concept of science.

I believe that most of us body psychotherapists are scared of the concepts ‘science’ and ‘scientific’, maybe for good reasons if we consider how the concepts have been used. Let me therefore address a big and quite complex question, or rather series of questions:

- What is scientific validation? Or how can the concepts science and scientific validation be defined?

- Does such a thing as a common consensus about this area exist?

- Do meta-scientists have a consensus concerning these questions?

As I understand this field of knowledge, the short answers to these questions, stated with a touch of humor, would be something like, Ouch! Oops! Not at all! And, Certainly not!

I am in no way a professional scientist or meta-scientist myself, but I do know enough – from my basic education as a psychologist and from my present work in the Danish Psychologists Association – to be fully aware that the terms ‘science’ or ‘scientific’ are used in many different, and in principle many correct ways as long as you are clear about your own position. Let me give some examples in the form of very short statements:

– Scientific is something that is ‘proven’ or documented as very likely correlations through quantitative, randomized and double blind investigations, and this only!

– Scientific is any clear well defined and self-critical description of a phenomenon no matter its size.

– Scientific is something several persons have written books about on a certain academic level.

– Scientific is something well known, and on which most specialists within an academic field agree that it is pretty good.

– Scientific is what professors at university do, or the academic subculture does.

– Scientific is an attitude that consists of elements like a self critical sense, knowing that man knows extremely few things with certainty, a non-judgmental openness to sensations or ‘facts’, willingness to alter and develop description and investigation methods with respect for the matter you are studying, and not at least, a willingness to have your hypotheses, descriptions and results investigated and discussed by others.

The above written statements are examples, expressing different modes of science, or different traditions within scientific thinking as there are:

- The quantitative or positivistic tradition, reflecting the ‘ scientific principle of correspondence.

- The hermeneutic or qualitative tradition, reflecting the scientific principle of coherence.

- Several social history and sub cultural context study examples, reflecting the principle of science that is called consensus

- And finally, an inclusive contemporary meta-scientific statement.

In practice, in the last more than forty years of academic investigation into psychotherapy, including discussions concerning what works best and most efficiently, the term scientific, quite bluntly, most often means that being scientific is understanding and describing ‘our way’; the professionals connect to one specific scientific tradition in one way of thinking, and unscientific is ‘all the other ways to do it’. You may say, that also within the scientific subculture, also the part that concerns itself with psychotherapy, there is an unsolved and ongoing conflict or disagreement about what is proper to do. On the one side we have a nature-science inspired positivistic tradition stating that only quantitative studies count; an attitude that has resulted in the so called ‘positive list’ of acceptable psychotherapies in USA.

On the other side we have a more humanistic-science-inspired attitude, stating that we need more case-describing studies (hermeneutic investigation) to understand what is actually going on in the therapeutic context, and what actually makes psychotherapy work. The latter attitude was the main conclusion on the latest congress arranged by the Society for Psychotherapy Research; the Chicago Conference in June 2000. Does this mean that we don’t have to pay attention to science, or that scientific validation is not important? No not at all, neither in my opinion, nor in the opinion of many of my colleagues, neither among body psychotherapists or academically trained psychologists. I, and many with me, believe that scientific validation is important, and a crucial task for psychotherapy in general and body psychotherapy specifically if we actually want the recognition from our contemporary society.

In addition to this inclusive and cooperative attitude, we find it crucial though to be critical and unimpressed by any kind of overdone attitude like”You are not scientific enough”, or “What you are doing is not scientifically based”. Statements like these are, you could certainly say, a violation of the very core of scientific thinking. I believe that we have to be humble facing the true and very complicated definition and practice of science. We especially have to be pretty clear what we specifically mean, and what we, as well as others, are specifically looking for when we ask for scientific validation.

To be scientific is neither to be imperialistic and dogmatic, neither to allow others to be imperialistic or dogmatic. To quote the well-known meta-scientist Michell, “The common core of all scientific methods is critical inquiry”. After discussing these matters, especially with scientists and meta scientist, it is my attitude that we should participate in, and if possible initiate as well, quantitative and qualitative scientific studies, with an open and critical, and as well as self-critical awareness of what kind of knowledge the different ways of working scientifically can provide and what they cannot provide. Is there anything we can do ourselves, to start validating our work? This question could be the cue for my next heading

A few steps in the direction of opening a dialogue with, and also exposing ourselves to the academic world.

I have some suggestions I want to share. Before doing that, I want to mention that I, as many others, have heard of smaller and bigger research-projects on their way. The EVA project is one of them. I am not up to date with knowledge about the EVA project or similar projects, but I certainly can support the idea of joining ongoing or upcoming research studies if you get the opportunity, and it feels attractive.

Joining such bigger research concepts is clearly a way to open a dialogue with broader professional groups.

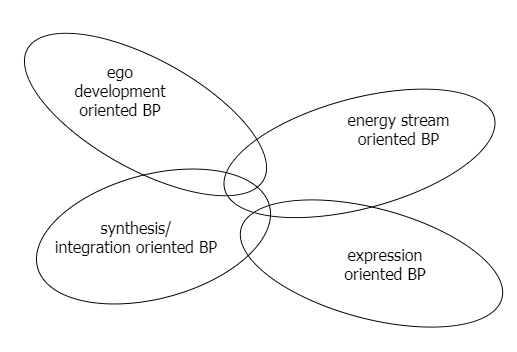

Now some other thoughts and ideas. I believe that stating a common ground of body psychotherapy, and additionally a simple mode of modalities of body psychotherapy is one of the most important presuppositions on our way towards a widespread recognition of body psychotherapy. So, I will risk my neck, and state some viewpoints on this vulnerable subject.

Suggestions concerning a model that describes the common ground of body psychotherapy as well as for four to maximum six sub-modalities of body-psychotherapy.

An understanding of the body as part of man’s being as a psycho-socio-physical entity has historical roots to the very beginning of psychology and psychotherapy, as we know it from the work of among others William James, Pierre Janet, Sandor Ferenczi and Wilhelm Reich. The EABP documentation as well as several papers on the history of body psychotherapy and psychotherapy offer more specific background and information. One model that in principle illustrates the common body psychotherapeutic understanding of man’s being as a psycho-socio-physical entity is the earlier mentioned Ego-Aspect-Model developed by Lisbeth Marcher. Another model, this one coming ‘from outside’ that might be helpful in developing a common ground, as well as a sense of different sub modalities of psychotherapy and body psychotherapy is the model ‘The Function of Consciousness’ developed by Soren Willert. Both these models are presented earlier in this paper.

I see body psychotherapy as a mainstream (modality) of psychotherapy, or, in other words, as a mainstream within psychotherapy. I find it reasonable to apprehend body psychotherapy as a mainstream of psychotherapy as well as cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy, family oriented and systemic psychotherapy, psychodynamic and psychoanalytic psychotherapy etc., although, this way of categorizing the field of psychotherapy is open to discussion. Just to give an example of my own field, Bodynamic Analysis – it certainly covers human everyday behavior, the actual social networks, the cognitive skills and characteristics and the psychodynamic development of the individual as crucial points of focus in the therapeutic process. Although we do emphasize a body related entry to the work with our clients and students. In my opinion it is not reasonable to talk about any of the different specific body-psychotherapeutic approaches as mainstreams of psychotherapy. Any of the maybe (maximum) 4 to 6 distinguishable and different approaches of body psychotherapy should in my opinion be considered as modalities of body-psychotherapy, and not as mainstreams of psychotherapy. As a suggestion one could imagine body-psychotherapeutic modalities as:

- Mainly psychodynamic oriented, or ego development oriented body psychotherapy;

- Body-psychotherapy mainly concerned with energy streams, pulsations and vegetative processes;

- Body-psychotherapy mainly concerned with human expression;

- Body-psychotherapy mainly concerned with an integrative or individual-synthesis oriented approach.

The most realistic way to illustrate this model graphically would be somewhat like the following, a model with some overlapping of the modalities.

Suggested modalities of body psychotherapy:

I am pretty sure that this discussion and hopefully, at some point, the agreement on a consensus on this question will be a very important step in the direction of an internal self-understanding in EABP, as well as in the direction of being seen and accepted as a mainstream of psychotherapy by professionals from outside.

Psychotherapy or bodywork

As body psychotherapists, we should be aware that bodily oriented ways of working have been used, and are used within a psychotherapeutic context as well as within several non-psychotherapeutic contexts. I have earlier used this example: A good Rolfing session is wonderful, and might very well be an important part of a personal developmental process, but is not psychotherapy. Whether a way of working with individuals or groups can be described with good reason as a kind of psychotherapy, depends on a series of questions about which there is no common shared consensus until now!

I will repeat what I see as some of the core questions:

- Is some clarified understanding of personality and person al development underlying the way of working in question?

- Are enquiry, problem recognition and problem analysis, and a clearly stated working contract between client and therapist part of the way of working in question?

- If so, is this working contract regularly followed up with a mutual evaluation of the outcome of therapy?

- Is the relation between client and therapist, including an awareness of transference and counter transference (or these phenomena described in other words) recognized and part of the teaching and the way of working in question?

Concerning the question whether bodily oriented work should be considered as genuine psychotherapy or treatment-oriented or development-oriented bodywork, I will suggest the following working model as a starting point: The questions who belongs where, who wants to develop in which direction, and, in the long run, who can be accepted by EABP and EAP as modalities of psychotherapy as well as who can not, have to be cleared, not later but pretty soon, and hopefully in a way that in the end leaves as few people as possible with a feeling of having been misinterpreted. I am sure, that a clear and ‘from-the-outside-understandable’ solution of these questions is necessary as a long-term presupposition in our striving for having body psychotherapy widely recognized as a regular mainstream of psycho therapy.

One last model to develop further is this theme:

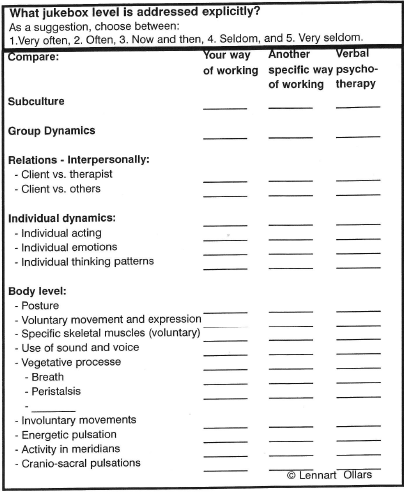

What do we explicitly address as body psychotherapists?

Remember the Jukebox Model? Two years ago, I started to develop this model further, especially by differentiating what you can address as a body psychotherapist. I will share this in a quite rough draft way with you, and invite you to think further, as I believe that this model could help us to differentiate between the different sub modalities of body psychotherapy. Our idea was to ask the crucial question: what layers are explicitly addressed in a certain mode of working? Any experienced physiotherapist knows that when he works with his clients he addresses bodily structures and then something often also happens with his clients’ emotions, self-understanding, and impulses to relate and express. He also knows that this fact does not make him a psychotherapist.

So, a way to characterize your way of working could be to investigate and clarify what ‘layers’ are addressed explicitly and not only implicitly. Asking this question, we could look at the Jukebox Model again, leaving out the top level, and, what is more important, try to further develop and differentiate the individual dynamics level and especially the body level. This would look like the scheme at the top of the following page. So far, my suggestions how to start differentiating between different modalities of body psychotherapy and possibly define the common ground of body psychotherapy. I hope we will dare to approach some of these questions soon.

Appreciating a scientific attitude on the level of practice.

One of the professionals with whom I have discussed scientific methods and attitudes in person, is the Norwegian professor in clinical psychology Geir Hostmark, a man who has the rare quality of being both a skilled therapist and a skilled scientist.

One of his points was that any practitioner can work to develop an open and self-critical attitude, or in other words a truly scientific attitude, in his daily work; looking with fresh eyes and openness at every new client, not taking his assumptions or ideas for granted, but registering how things actually work out, try to find new ways in cooperation with your client, be open to how reality develops, reflect on what happens and adjust and readjust to reality, and be aware of the limitations of your methods and skills. Working like this is unfolding a scientific attitude on the level of practice. Geir Hostmark suggested calling this attitude ‘working as the reflective clinician’.

By using this term Hostmark is referring to a very interesting book by Donald Schon from 1983 with the title The Reflective Practitioner – How Professionals Think in Action. Schon’s main message is that most of our interventions are guided by a kind of ‘silent knowledge’, using here a concept from the philosopher Poliany. Schon also suggests that we start talking about ‘reflection-in-action’, and ‘reflection-over-action’ as two different ways professionals, including psychotherapists, have to work in order to succeed. It is my experience that many body psychotherapists already do this; working with a pretty open mind and a truly scientific attitude; with curiosity, an open awareness of outcome and respect for the effect of their interventions.

I believe that working with the body both requires and also develops this open-to-outcome attitude. What I am trying to say with this introduction to the concept ‘reflective clinical work’ is that we have already started on a very important path. What we need to do in addition is firstly to recognize and appreciate this ‘from moment-to-moment-tracking-reflecting-acting-process’ and then start describing it and discussing it.

A simple suggestion: rent a TV camera, video-tape a couple of sessions, and then discuss what is happening in the client, in you and between both of you, firstly by yourself then with a couple of close colleagues. Initially rather do this as a kind of ethnographic project instead of looking for what ought to be there according to usual or presupposed models and thinking.

This would be a little piece of ‘studying the non-specific factors’. Which is actually the kind of qualitative scientific research mostly needed. I can imagine your protests: “I’m not a scientist, it takes much more… etc.”, and this is true of course in many ways, I know. But still, it would be a nice start.

Starting a critical inquiry and dialogue

The next necessary step towards an un-judgmental and critical dialogue, or you could say going public with our scientific quest, is simply to describe and show in print and in vivo your practice and your theory, it’s implicit and explicit ways of understanding the human nature, the resulting working models and methods, and your guidelines for therapeutic strategy and intervention. To say it in a short and practical way: write down what you have seen on the video, and show this together with the video to other body psychotherapists and other psychotherapists, and why not to a dancer, an ethnographer and…

Probably the most crucial part of this is to enter a critical dialogue with colleagues and other professionals, or to invite and allow others to discuss our actual interactions in sessions and thereby also our presuppositions, our methods and our theory.

Many of us have already started this work – the work with presenting and writing. This is one of the things we actually do at symposia and congresses, when we present our papers and our way of working.

One aspect that is still missing though, as I see it, is to find a way to discuss and to be critical, a way to start a dialogue that goes beyond politeness or silently shaking our heads. We have to find ways to be more challenging, critical and to discuss and dispute. And we need to get more feedback, and critical reflections from other professions.

Ideas on how to start more critical dialogue, orally or in writing.

I have mentioned the idea of a critical panel, to be used on conferences or other meetings. In addition to your presentation the planning committee may invite let’s say two ‘opponents’ to comment on your presentation, from their point of view. These comments are then followed up with a discussion. I remember that Will Davies tried to get through with something like this idea. I believe it was on the Pamhagen Conference. He had brought a video, and tried to convince several of us to see it, outside of the scheduled conference agenda, and he even asked for critical comments. So a group of approximately 6 people saw the video and had a short discussion even though the circumstances were a bit stressed. As I remember the situation, we didn’t really have the time or the form to get full satisfaction from it. But I still remember this hour as pretty meaningful.

I believe we need more of this kind of thing on our conference agenda’s, and with enough time scheduled, maybe in a form that includes both personal reactions and a content discussion. Maybe the idea of opponents or a critical panel could be used in journals to. In fact this year I have learned about a Journal published at the University of Arhus, where they use a model like this. Each edition of the paper contains as the core content:

- A target paper (a presentation).

- A series of written comments from other professionals (say five or six).

- A first written reaction from the target author.

We might learn from this model.

I have used another method several times, with a good outcome. When I have been writing a paper on some professional subject, I have often got feedback from close colleagues, but in addition to this I have occasionally asked a professional in my network, but explicitly with some distance to me for feedback. Several times I have chosen someone with a more strict academic way of thinking than mine. This has been a bit challenging, but also very helpful. The more we dare to ask professionals other than our friends to join a critical dialogue, in person and in oral discussions or in writing in some other form, the better.

Writing-difficulties and more ideas to get started.

Now I am so stubborn, gifted and lucky that I have crossed the first ‘writing-barrier’, but I know that this is not the case for everyone of us. It is a widespread experience that most professionals, including psychotherapists, are reluctant to write, maybe even especially so when it comes to writing about their work. This fact certainly is true for academic psychologists too. In professional educational contexts psychologists often wonder why most professionals write absolutely nothing, after they have finished the mandatory thesis stuff during basic education or following further educational programs.

The most obvious reason for not writing, apart from the fact that it unavoidably takes some time and energy, is probably a fear of not living up to the unspoken norms of ‘real science’ or ‘profound thinking’, etc. It has been my experience though, that if you dare to share less ambitious thoughts, like a case story, a few reflections on a subject, etc., you actually get a lot of good feedback from the professional network. Not from most university academics, but rather from other practitioners. But that’s a good enough start.

This will only work in some journals of course. It will not work in the ‘hard core’ scientific journals, but likely in newsletters, association journals and probably in Energy & Character or the new Journal (hopefully coming soon) from EABP and USABP. Why not form some groups of body psychotherapists that want to meet with this problem in focus and give each other some support and maybe pay for some help? One part of this would probably turn out to be sharing and working on writing-blocks. Another obvious part could be writing little fragments and discussing them. When it comes to the content, I would suggest case stories or a few reflections as mentioned above. Some years ago I saw a series of ‘spots’ concerning ethics in practice, written by a Danish psychologist in our Danish Psychologists’ Association Journal. Later that gave me the idea to write a series of ‘spots’ (spots explicitly defined as fragments, and not as any kind of total overview) on supervision. It was accepted, and this was one of the ideas, which I got a lot of positive feedback on.

This year I have suggested a 5-module workshop for the Danish Association of Psychologists with the title ‘Psychotherapeutic Practice in Perspective – Critical Reflection and Qualitative Research for Practitioners’. It is a workshop spread over almost a year, and it is supposed to be led by an experienced academic researcher and myself (as the other polarity; a practitioner with some writing experience). Whether the idea will be realized next year or later is not settled yet. I might consider offering this workshop within EABP. Time will tell, but the idea is free to copy for others.

Researching outcome of therapy.

Contemporary research on the outcome of psychotherapy is most often based on substantial studies, involving many clients and many therapists. But this is not the only way to do outcome research. As I have suggested small qualitative case studies are needed as well. Here is another possible and not too demanding idea: At one of my meetings with Geir Hostmark (mentioned above), I asked him directly if he could suggest some well known outcome-evaluation-scale you might use to ‘measure’ the outcome of psychotherapy. One of Geir Hostmark’s merits is that he has been conducting some pretty big out come studies in Norway (Hostmark 1988). His answer was strikingly radical. He said, “Make a new scale for each client “! And then he elaborated that as we know pretty well from research that the outcome of psychotherapy is heavily dependent on the presuppositions of the individual client, of the characteristics of the individual therapist and finally on the quality of contact between both.

It seems pretty interesting to make a specific measuring scale for each therapy process. So ask your client what is important, and construct a 1 to 5, or a 1 to 10 scale in cooperation with the client, maybe after a couple of initial sessions. This would be a helpful part of making a solid working contract any way, and could also function as a tool to evaluate the out come! Great idea. Five therapists in the Bodynamic network will try this idea out in a small pilot project during this autumn and spring 2002. If it turns out to be workable, we plan to spread the model to a bigger group of therapists, and maybe apply for money to include external evaluators/statisticians/researchers.

The idea is free to copy of course. I would really like people to try it. And I would certainly like to hear about the outcome! Probably it will not be quite as easy as it sounds initially. Just think of what often happens in a therapy process; quite often a client will formulate his wishes and direction in one way when he starts, and the outcome after 6 months might be in quite other words. But if this happens in our pilot study we will try to track it and describe it, because after all it is the real thing we want to describe.

The importance of relating our work to common professional language.

I will just repeat briefly what I stated earlier. If we want to get into a dialogue with other professional therapists, we have to use some of the commonly shared language – not exclusively but additionally. We probably have something to offer to the commonly shared psychological language because we have so many experiences with bodywork, but we also have to accept the challenge both to try to develop and polish our own language and to learn to use more common language in describing our work, our methods and our theory. Just to remember that we don’t have to do all the work ourselves, I will mention one more way to get in dialogue with other professionals.

Invite other professionals, maybe even researchers in. It is obviously an idea to invite somebody from outside to look at, to describe and comment on and maybe research into what you are doing. A number of times I have been lucky enough to encounter professionals from outside my own network, who have attended my work, or that of my colleagues. Occasionally we have been offered interesting comments from outside. A few times we have followed up on this, and it has mostly been very interesting and helpful for us in our long-term work with describing what we are doing. I am convinced that the time has come, that this kind of ‘cross-network-and-tradition-dialogue’ is one of the most fruitful steps we can make! So I strongly suggest inviting other professionals in, and asking them specifically to pay back with comments, preferably written, and then spend some time in dialogue. Maybe we can even be so lucky now and then that professionals from outside are willing to investigate more systematically or to research into what we are doing.

As an example, a few years ago, in 1998 we were so lucky in the Bodynamic Institute, that the Danish sociologist Eva Brendstrup, working at the University of Copenhagen, offered to do some research into the outcome of Bodynamic Analysis. The main focus of the research was on the effect of Bodynamic Analysis on psychosomatic symptoms. A written report is available, in Danish. At this point of time I believe we should do our utmost to invite scientists in.

Hopefully time is more ready for cross traditional dialogue?

I have the hunch that the time is ripe for dialogue and cross tradition thinking. It seems as if there is a new overlap area growing between psychotherapy, research in and treatment of PTSD, research in neurology and brain function and research in immunological systems – an overlap area where more and more professionals understand that a dialogue across traditional professional boundaries is needed. I know that there is a growing wish among some psycho therapists to start thinking more interactively and across traditions.

On Danish ground, Esben Hougaard, a respected professor at The University of Arhus reserved several chapters in his book on theory and research, in psychotherapy (1996) on the layout of a more integrative way of thinking. Esben Hougaard is traditionally very much for cognitive models, but nevertheless inviting to a more integrative cooperation. Cognitive oriented psychotherapists are by the way very interested in what happens in the body, along with what happens in the mind, and work explicitly with what they call ‘psycho educative’ techniques helping the clients to handle themselves better.

Alice Theilgaard, who is a doctor in medicine and former professor in clinical psychology in Denmark, and well known and respected in the psychoanalytic network both in Denmark and internationally, wrote a paper last year called ‘The Neglected Body’. In this paper, which is now pretty widespread among psychologists in Denmark, she argues for the importance of integrating body sensations and body language in clinical work.

Finally, as I have shared with you earlier, recent research in psychotherapy suggests that there is more interest in studying the non-specific factors that make psychotherapy work. It sounds to me as if this is an invitation to think and investigate more across traditional modalities of working and understanding within psychotherapy. Let’s join and support this tendency to open dialogue between traditionally more separate professional sub-cultures, and across different modes of psychotherapeutic thinking. Let’s stick out our necks and invite more professional dialogue. I know we have a lot to offer and I am sure we have a lot to learn.

The message in essence

In summary, it is my suggestion and message that, as much as we possibly can, we invite an open and critical dialogue among ourselves as well as in contact with other professionals. In this dialogue, we should both be guided and guide others to think as open mindedly as possible. In other words, we should try to adopt and develop a truly scientific attitude on the level of practice as well as we can.

The scientific attitude on the level of practice is as suggested by meta-scientists, an attitude that consists of elements like a self-critical sense, knowing that man knows extremely little with certainty, a non-judgmental openness to sensations or ‘facts’, willingness to alter and develop describe and investigate methods with respect for the matter you are studying, awareness of the limitations of any method and theory, and last but not least, willingness to have your presuppositions, descriptions and results investigated and discussed by others.

© Lennart Ollars, September 2001

References:

Asay and Lambert, The Empirical Case for Common Factors in Therapy: Common Findings in: Hubble, Duncan and Miller.

David Boadella, Awakening sensibility, recovering motility. Psych-physical synthesis at the foundations of body psychotherapy: the 100 years legacy of Pierre Janet (1859- 1947). International Journal of Psychotherapy, vol 2. no. 1 1997.

Eva Brendstrup, Klienter i Bodynamic Analyse. Sociologisk lnstitut, Kbh. Universitet: July 1998.

William P. Henry, Science, Politics, and the Politics of Science: The Use and Misuse of empirically Validated Treatment Research. University of Utah. Psychotherapy Research 8 (2), 126-140, 1998.

Esben Hougaard, Psykoterapiteori og forskning. Dansk Psykologisk Forlag, 1996.

Hubble, Duncan and Miller, The Heart and Soul of Change, What Works in Therapy. Washington, APA, 1999.

Geir H0stmark, Relational Psychodynamic Practice is supported by evidence: An examination of certain assumptions in the debate on treatment effects. University of Bergen.

Geir Hostmark et al, Brief Dynamic Psychotherapy for Patients Presenting Physical Symptoms. Psychosomatic Psychotherapy, vol 50, 1988.

Jarlnces, Marcher and Ollars, The Scientific Validation of Bodynamic Analysis. Copenhagen, 2001.

Lennart Ollars, Supervisor spots. Danish Psykolog Nyt nr. 2- 8, 1996. Seven short papers on the therapy process, the therapist role and supervision (in Danish).

Agnes Petocz, Psychology, science and the symbol. The Meaning of Science ad the Science of Meaning: Implications for Psychological Practice. University of Western Sidney Macarthur, Australia.

Donald Schon, The Reflective Practitioner Basic Books Inc.

Alice Theilgaard, Den negligerede krop. Matrix 17. argang 2000, nr. 2, s. 137-151.

Soren Willert, The Function of Consciousness: Biological, Psychological and Organizational Perspectives.

Presentation at the Tucson Conference Towards a Science of Consciousness, April 2000.

The model is described (in Danish) in: Bulletin for Antropologisk Psykologi, no. 7, 2000.

Irvin Yalom, ‘Love’s Executioner and ‘Lying on the Couch‘