Bodynamic Analytic Work with Assault and Abuse

By Lennart Ollars

What is the impact of incorporating work with the body in the therapeutic treatment of assault/abuse? Victims of violence or sexual abuse who have tried to work it through exclusively in verbal therapy often express: “I know what happened, and I have talked it through, but I’m still missing something.” “I can’t seem to be finished with it.” “I still don’t like my body.” “I’m still scared.”

Body-psychotherapeutic work with victims of assault/abuse usually enables radical progress. First the client will experience the assault/abuse as more “real” — the experience gains a somatic and emotional reality. Later s/he will find it is actually possible to release the experience: feelings can be expressed, nausea and anxiety disappear, the stomach becomes quiet again, etc. The client learns that the bodily experience can be changed.

We believe assault/abuse is always a traumatic “shock” which leads to a state of post-traumatic stress (PTSD — Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder — See: DSM III.) and requires therapeutic intervention (See: Jorgensen, 1992).

First, I will sketch the aspects of therapeutic work with assault/abuse that are emphasized in Bodynamic Analysis:

- Before therapy can begin, the therapeutic space must be established; a base of trust must be built and preserved. This is necessary in all types of therapy, but more so in body-psychotherapy where the risks, as well as the potential for growth and change, are greater

- In general, it is beneficial and sometimes necessary to help a client to better understand his own personality dynamics. One path from shame and guilt to self-acceptance is through understanding.

- In Bodynamic Analysis we help the client to recognize and, to a limited extent, relive the assault/abuse. We work with a precise and bodily-anchored reconstruction and reorganization of the traumatic situation, making it possible to release and restore emotionally and physically held energies. The assault/abuse “dissolves” — emotionally and physically — step by step.

- We also work to reestablish the original/”healthy” orientation and movement reflexes by developing potential for the bodily-anchored emotion and action which was arrested as a consequence of the assault/abuse.

- Victims of assault/abuse have — somewhere inside — an anger and desire for revenge that is equal in violence to that which they experienced in the assault/abuse. We uncover that power by recognizing, working through and integrating polarities. This process often includes working with “out-of-body” experiences connected to the assault/abuse, and, of course, with “coming back” to the body and re-identifying with it.

- Assault/abuse usually leads the victim to making one or several, often unconscious, decisions. These must eventually be exposed and redecided.

- Contact and the field of contact in the therapy must be worked with in several dimensions:

- The client must have help to contain feelings about the assault/abuse.

- The client must share the reality of what happened with others. Often neither family nor friends have “seen” or understood what really happened.

- Therapy must include the establishment of the help that was lacking in the assault/abuse situation.

- There is continuous work to reestablish constructive relationships with others, i.e., establishing a basis for slowly rebuilding trust to a decent father/man and/or mother/woman, friends who believe and support, etc.

- This last aspect is especially important when working with sexual abuse or incest. In this instance, it is important to work with therapists of both sexes.

A special situation exists where the client has been witness to other’s being assault/abused. Here it is necessary to work with the shame that develops from being helpless in preventing what happened. The client needs help to accept and forgive his powerlessness.

Lastly, it is necessary to work with developing an understanding and grasp that assault/abuse can happen. This includes helping the client to find a reasonable balance in his/her life: including judgment skills and a realistic degree of mistrust — without the loss of belief in the potential and value of human relationships.

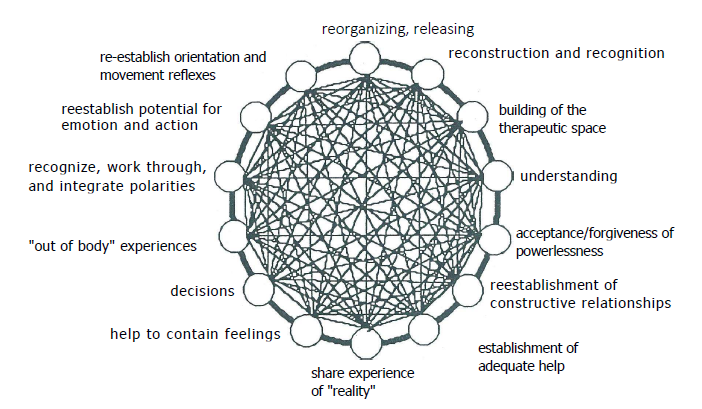

Many of these aspects of Bodynamic Analytic work with assault/abuse will be expanded in the rest of this article. They are neither chronological nor prioritized in the therapy. Each aspect is connected to and partially overlapped with the others. The therapeutic focus changes from session to session. How these aspects are addressed in practice, is best illustrated by the figure below.

Dissociation as a Psychological Defense

Dissociation is a usual defense mechanism after an experience of assault/ abuse. All therapists are familiar with the memory loss and blocks to accepting the reality of a trauma that follow such experiences. The earlier the event, the more ambiguous -possibly idealized — the childhood has become in the mind of the victim, the more difficult the process of remembering will be. It is also common to remember the event, but dissociate the emotions, impact or consequences tied to it. An attempted rape, mugging, incest or incestuous relationship may be remembered clearly, but without emotional and physical reality.

Incorporating the Body — Recognition, Reorientation, Reconstruction

In Bodynamic Analysis we use body awareness to help recognize and reconstruct the assault/abuse — often by assuming the same physical position as in the original traumatizing situation. Attention to position and posture is very detailed and proceeds slowly, step by step with high regard for the client’s readiness. At the same time the experience is reorganized by helping the client to, now, react differently, adequately, “healthy”. Reorganizing during reconstructing is essential if one is to avoid — what is least wanted — repeating the trauma in the therapy office. The therapy “changes” the inner experience to what could have happened if appropriate response/help was possible.

Precise work with the body leads to reorganizing or “releasing”. An example: In a particular assault/abuse position several different muscles are tensed and movement is limited, the breathing stops. Reconstruction of this particular position helps the client to recognize the psycho-physical defense pattern that was activated in the assault/abuse. Illuminating the details of tension and blocking creates potential for a, now, healthy somatic response. Bringing attention to exactly where and how the response became stopped in the body, allows the response to, now, be completed.

Reestablishment of Orientation and Movement Reflexes

It is usual that an assault/abuse victim’s instinctive orientation reflexes are damaged: i.e., after a blow, the body often tenses in several muscles including areas of the throat, neck and around the eyes. If these tensions aren’t released, the victim’s ability to orient himself becomes decreased. Therefore, we work systematically with rebuilding the client’s orientation skills. We are greatly inspired by Peter Levine in our understanding of the effect of shock/post traumatic stress on the body’s basic reflexes.

Similarly, movement reflexes are also decreased after an assault/abuse. Especially when the victim was restrained, for example, will impulses to break loose and run away be damaged. It is often necessary to reestablish these reflexes to act defensively. We often work specifically to reestablish the running reflex (See: Jorgensen 1992).

Working Through and Integrating of Polarities

Violent or sexual assault/abuse causes, in its victim, not only anxiety and resignation, but also a violent rage. This is not an adult, contained anger, but a violent, unbounded hate with an accompanying desire to smash, kill and destroy. The degree of rage tends to correspond to the degree of violence in the assault/abuse. Often this desire for revenge is equally as frightening as the assault/abuse itself. It is important to work through, as a crucial step out of the victim role.

Working with this rage on a body level is helpful and usually necessary. Rage must move — hit, kick, etc. — within a well-structured environment that includes emotional contact and acceptance. It goes without saying that a secure therapeutic structure is necessary for recognition and release of this rage. It has no place in the client’s daily life. Structure and security are also necessary before a victim will “dare” to work with it. Work with this rage must be step by step — releasing and integrating slowly to avoid further overwhelm or damage to the ego or self-concept.

Some of this rage may also be the result of shock. Flight is one of the two possible reactions to danger; fight/attack is the other. Part of the reason the client’s rage can seem overwhelming is that it may be a biological response to danger. (See: Jorgensen 1991 and Levine 1990/91.)

Reestablishing Potential for Contact, Emotion and Action

This side of somatic work with assault/abuse is equally important. “Health”, happiness, lust for life, etc., are often given up or displaced in assault/abuse and are hidden “under” or “behind” the experience. Curiosity and enjoyment in exploring the city can, for example, disappear completely or partially after a mugging or mugging attempt. The desire to be touched and pleasure in one’s own sexuality are often diminished or absent after a sexual assault/abuse. We don’t consider therapy to be complete until the desire, happiness, curiosity, and other resources that “lay under” the traumatizing episode are uncovered and recaptured again. Precise body-psychotherapeutic work is invaluable in reestablishing these emotions and their bodily expressions.

Precisely where and how is it nice to be touched? Where and how do you sense desire? Where is it also a little dangerous? How do you sense and express these nuances? Such questions are a partial example of this phase of the therapeutic work. Re-experiencing desire for physical contact, may seem more frightening for the victim of sexual assault than thinking about the past abuse. But I repeat that it is crucial to help the client in reestablishing enjoyment of his own body. Of course, the client must choose for himself how he will live his life and how he will interact with others. But the therapist must regard both the resolution of past problems, and the future potential for life and contact.

Decisions

The decisions the victim has made in response to one or several assault/abuses determine the turn the therapy will now take to help secure the victim’s future. Decisions as, i.e., “I will never lose control in sex again.” “It is dangerous to be happy.” “When I express my sexuality, I get abused.” are common and can, if not uncovered and worked through, seriously limit the victim’s life in greater degree than the visible effects of the assault/abuse.

The Therapeutic Space

The field of contact between the therapist and client — degree of trust, what is ok and not ok, who has responsibility for what, etc. — is always important no matter what method of therapy is used. In body-psychotherapy, there are aspects of this contact that are especially in focus: How do the client and therapist lie or sit, and at what distance from each other? Where and how is touch allowed? etc.

It is easier, but also less complicated, to trust a therapist who always sits in a chair at the same distance. Trusting a therapist who may touch you is more difficult. The body- psychotherapy client is forced, with the therapist’s support, to sense the nuances in what is secure, pleasant, ok, dangerous, nice, frightening.

In Bodynamic Analysis we work a lot with this field of contact and find it especially meaningful in work with assault/abuse which is always a bodily invasion. A client who previously could feel secure sitting 6 feet from the therapist, may suddenly feel relieved withdrawing to a distance of 15 feet and wrapping himself in a blanket. A client who would never be touched, may recognize precisely which kind of touch feels bounded and pleasant, and which is unbounded and unpleasant. Attention to the physical aspects of the field of contact will allow for greater nuance and depth in the therapy.

Clear and Unspoken Boundaries

In Bodynamic Analysis we take it for granted that it is the therapist who is responsible for the therapeutic boundaries. Child abuse and incest, especially, are full of manipulation, seduction and destructive symbiosis: “You like that, don’t you.” “This is our secret.” “You know how badly mother treats me.”, etc. Invasion of boundaries also occurs in cases of sexual abuse with teens and adults. It is therefore crucial for the therapist to actively and explicitly talk about respect for boundaries, and to take responsibility for keeping healthy boundaries.

Unfortunately, we all know of clients who have been sexually involved with a therapist — usually clients with histories of invasion of boundaries. There is no excuse for such behavior by a therapist, not even that an adult is responsible for him/herself. A therapist who has sex with a client, workshop participant, or student runs a monstrous risk of repeating and locking in an assault, incest or abuse problem. “Therapist Incest” is a crude, but often (seen from the client’s view) fitting description for this type of invasion. Luckily, sexual boundaries are finally being included under the ethical rules of various psychology associations. Let’s hope it helps. And until it has helped, let’s talk openly among our colleagues about the therapist’s responsibility for therapeutic boundaries.

Clover Southwell has written an outstanding, clear, and varied article about sexual boundaries in therapy. I highly recommend this article. It preserves both the value of sexuality as one of the rich sources of life and the necessity of keeping the sexual boundaries in the therapeutic relationship.

Witnesses to Reality

One of the characteristic side effects of sexual abuse and incest is the creation of taboo and its accompanying secrecy and silence. This makes it difficult for the victim to recognize totally and fully that the abuse really happened. In Bodynamic Analysis we ask the victim to invite friends to the therapy. They expand the victim’s field of contact about the abuse. The friends serve as witnesses and support for the victim and his reality of abuse, and as helpers in working it through. They support and confirm the victims experience of reality.

Getting the Help that Should Have Been There

The consummation of an assault/abuse implies that the victim couldn’t defend him/herself or get away on his/her own, and that no other help was forthcoming at the time. This is most extreme when children are attacked or abused, but may be equal in degree — though not as obviously — when adults are assaulted/abused. We acknowledge that such an assault/abuse couldn’t be handled alone. The introduction of “help”: e.g., one or several adults should have helped the child (or adult) back then, is necessary for reorganizing and developing a healthy imprint on the situation. Therefore, we frequently use one or more “helpers” in the therapy. Their role may be to help by, i.e., pushing away, yelling “stop” at the attacker, etc. The experience of getting help enables the victim to react in a healthy way (tear loose, run away) and serves as a basis for building up trust to others in the present. Our use of witnesses and helpers has been inspired by the American body-psychotherapist, Al Pesso.

Re-Parenting — Rebuilding of Trust

In extreme abuse, e.g., repeated sexual or physical abuse with children, the victim can be said to have been doubly betrayed — both by the offender of the one sex (perhaps the father), and by the potential helpers of both sexes (perhaps the mother and/or other family members). Therefore, in Bodynamic Analysis we find it useful for the victim of these kinds of abuses to work with therapists of both sexes. Work with both a man and a woman therapist is necessary to fully rebuild trust. The client may end therapy with a therapist of the one sex and continue with another, or while maintaining relationship to the primary therapist have periodic sessions with another.

Another possibility is a group or workshop with therapists of both sexes. Therapy in these settings have other advantages, including the possibility of working with peer contact. This way the victim can experience that assault/abuse can be revealed socially without catastrophe.

When the abuse is with a child, much of the therapy must include re-parenting, a lengthy rebuilding of trust to both men and women, independent of the sex of the offender. The child was doubly betrayed if, for example, the father committed incest and the mother “ignored” it, or the child’s reactions. Consequently, therapists of both sexes and helpers of both sexes are necessary to rebuild trust.

Assault/Abuse — Often Only a Part of the Problem

Single standing assault/abuses are possible: i.e., a woman was raped, or a man was beaten by a gang while on vacation. But most often a victim has experienced several assault/abuses. One violation makes the victim vulnerable to others.

There are children who after being assault/abused have received all of the support from their family that anyone could wish. But, unfortunately, it is more common that a child victim of assault/abuse who tried to send signals for help, was not “seen”. The adults could not or would not see or hear the child’s cry for help.

Such histories reveal that the family’s patterns of dysfunction existed long before the assault/abuse. “Healthy” parents will recognize that something is wrong. A family that fails to see the resulting difficulties of an assault/abuse, have usually failed to see many other of the child’s difficulties and needs. Emotionally poor relationships with many other types of betrayal or neglect often lay behind a history of assault/abuse. Neglect often lies unseen behind an idealized front. Therefore, it is often necessary to broaden the scope of therapy with assault/abuse. This makes the process longer, but not at all impossible.

Understanding – Grasp of One’s Own History

It is beneficial to support a client in his understanding of the interrelated dynamics in both his childhood and adult life that “lay behind” his current strengths, difficulties and sense of self-worth. It is common for assault/abuse victims to struggle with feelings of shame and inferiority and to have difficulty in holding boundaries and setting limits with others — easily experiencing other’s needs as much more important than their own. When a client gradually understands and accepts that these reactions are the result of, for example, repeated abuse, it becomes easier to move from self-judgment to self-acceptance. Understanding cannot replace the bodily anchored, emotional working through of assault/abuse, but it is part of a cognitive container of reason which helps make the working through and rebuilding of a new self-concept possible.

Chronology of Work with assault/abuse

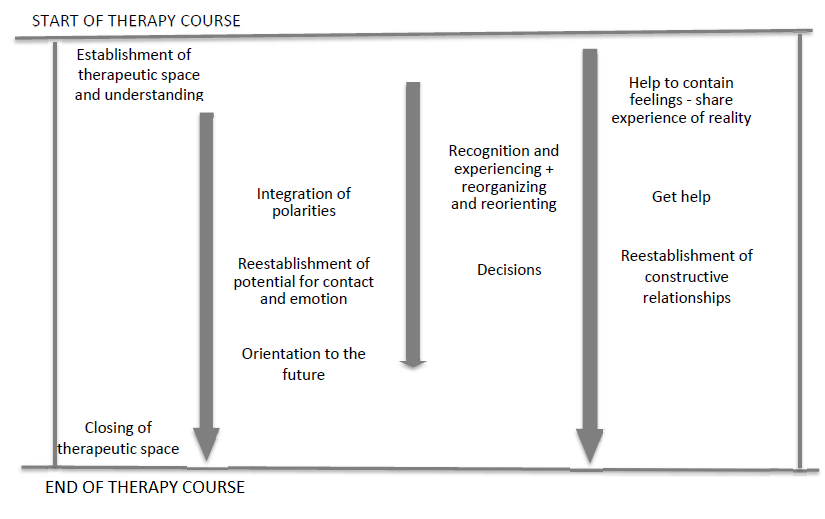

This article began with a review of the aspects of therapeutic work with assault/abuse. These aspects appear several times in the course of therapy. However, some of the themes are more central in particular phases of therapy than others. I will conclude this article with the following figure which arranges these aspects of the work chronologically.

References:

- Virginia Wink Hilton: Working with Sexual Transference. Bioenergetic Analysis:The Clinical Journal of the International Institute for Bioenergetic Analysis. Vol. 3, No. 1, 1987.

- Steen Jorgensen: Bodynamic Analytic Work with Shock/Post Traumatic Stress. Energy and Character, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1992.

- Steen Jorgensen: Chok/Posttraumatisk stress: Symptomer og &sager. BODYnamic Institute, 1991.

- Peter Levine: The Body as a Healer. Somatics Magazine – Journal of The Bodily Arts and Sciences. Vol. VIII, No. 1, 1990/91.

- Albert Pesso: Abuse. Energy and Character, 1989.

- M. Bentzen, E. Jarlnaes, P. Levine, L. Marcher: The Body Self in Psychotherapy. A Psycho-motoric Approach to Self Psychology. Unpublished manuscript.

- Lennart Ollars (Ed.): Muligheder i kropsdynamisk analyse. BODYnamic Institute, 1990.

- Clover Southwell:: The Sexual Boundary in Therapy. Energy and Character, 1991.