THE BODYMAP – A PRECISE DIAGNOSTIC TOOL FOR PSYCHOTHERAPY

by Peter Bernhardt, MFCC, and Joel Isaacs PhD

ABSTRACT

In this article we introduce readers to the Bodymap, a precise diagnostic tool developed as a part of Bodynamic Analysis. The Bodymap is a concise visual format for displaying and analyzing psychological information stored in the muscles. The ability to measure muscle responses and access the historical information they contain makes a developmental analysis in terms of psychological character structures more concrete and less metaphorical. We also introduce ten “Ego Functions” (e.g. grounding and reality testing, centering, cognitive abilities, self expression, etc.) that are used to understand human functioning. The Bodymap can also be read for the presence or absence of resources corresponding to these ego functions.

Outline of The Bodymap Article

Outline of The Bodymap Article

INTRODUCTION

Part I. THE UNFOLDING OF MOTOR DEVELOPMENT

Part II. MUSCLE RESPONSE AND FUNCTION

Part III. THE BODYMAP

Part IV. ANALYSIS OF A BODYMAP

Part V. THE SEVEN DEVELOPMENTAL STAGES

Part VI. THE TEN EGO FUNCTIONS

Part VII. BODYNAMIC ANALYSIS AND THE BODYMAP

Part VIII. A SESSION – USING THE MAP

Part IX. AN ANALOGY

REFERENCES

APPENDIX 1. HISTORY OF THE CONCEPT OF MUSCLE RESPONSIVENESS.

APPENDIX 2.

- Figure 2 A BODYMAP,

- Figure 3 THE WILL STRUCTURE,

- Figure 4 THE EGO FUNCTION “CENTERING”

APPENDIX 3. THE BODYNAMIC CHARACTER STRUCTURES (chart)

APPENDIX 4. THE TEN EGO FUNCTIONS

INTRODUCTION

Danish psychotherapist Lisbeth Marcher and her colleagues have been contributing to a new language for body psychotherapy based on a more detailed psychodynamic knowledge of the body than either Reich (1) or Lowen (2) had available. A step towards a new language was taken by Marcher and her colleagues when they created a detailed, articulated, structured theory based on twenty five years of clinical experience and research into child development and adult functioning. The resulting theory and methodology, Bodynamic Analysis, integrates psychomotor theory, depth psychological theories, and Reichian and Lowenian character structures, with original, detailed, empirical research into the psychological content and developmental timing associated with individual muscles. While body psychotherapies often work directly with emotional and energetic processes in the body (1,2) Bodynamic Analysis starts with a detailed analysis of a person’s measured muscle responsiveness, and goes on to work primarily with his character structure, shock trauma, and ego functions as they affect the client’s life.

This article continues our presentation (3, 4) of how a modern knowledge of human functioning is contributing to the development of a new language for psychotherapy. An important part of this language becomes available when the body is included as part of psychotherapy. Understanding how historical information is encoded in the body, particularly in the voluntary musculature, offers a more direct access to a person’s understanding and experience of himself. A knowledge of anatomy, of the muscles and their psychomotor functions, allows one to “speak the language” of the body, allows one “to dialogue with” the body at a primary process level. In contrast, most verbal psychotherapies are based on a person’s secondary process, their own verbal descriptions of themselves.

These contributions to a new language also reflect how the body and the psyche interface during childhood development. While the traditional language of psychotherapy often reflects a negative view of people’s resource or survival systems (Freud, Reich, etc.) newer approaches attempt to mirror the experience of a child relating to the world (5). This newer language is focused on the body, on interpersonal interaction, and on the development of a healthy, capable, flexible personality.

In our experience, including the body in psychotherapy greatly facilitates the process of uncovering subjective experience. The body, specifically through access to the muscle imprints, can link theory and practice, the abstract and concrete, the verbal and nonverbal or preverbal, clinical insight and client behavior. Therapeutic approaches that do not attend to the body, that are verbal only, are often using words and emotional resonance to evoke states, memories, and experiences that were pre-verbal or have a large non-verbal component (6).

colleagues – Along with Lisbeth Marcher, the original Bodynamic Institute members in Denmark include: Erik Jarlnaes, Marianne Bentzen, Merte Holm Brantbjerg, Steen Jorgensen, Lennart Ollars, Ellen Ollars, Sonja Fich, Bente Morup, and Lone Reimert.

developmental timing – By this we mean the age range in which the particular muscle first comes under conscious control. Before this time the movement associated with the muscle may be controlled by reflex action.

I. THE UNFOLDING OF MOTOR DEVELOPMENT

Central to Bodynamic Analysis’ understanding of human behavior is its hypothesis about the central motivation in human development. Noting that a child is imbued through the course of development with immense resources for living, it is postulated that the central motivation is expressed through an innate desire to establish rich, complex and passionate relationships with self, parents, peers, community, animals, nature, the larger world, and the spiritual world (7). Marcher has called this innate drive to relate “mutual connection” (8). Mutual connection is expressed through the resources of the body: through the sensory-motor system, through emotion, and through thought.

A newborn child is dominated by motor reflexes, and voluntary control of muscles largely does not yet exist. As the child ages, specific muscles begin to come under voluntary control. The newly learned abilities of lifting and turning the head, sucking, rolling, creeping, crawling, and grasping each require control of new muscles. The child’s increasingly complex and subtle activities – motoric, social, psychological, cognitive, and verbal – are expressed through her increased motor control. The child learns to hug, and also to push away things she doesn’t like. She learns to balance herself using small muscle movements while standing or walking. Her hand grip continues to develop until around six or seven when true writing becomes possible.

Marcher and her colleagues asked the question: “At what age does each muscle come into play developmentally?” By this is meant the age or age range in which a particular muscle comes under voluntary control, as evidenced by a particular developmental movement or ability. This knowledge is available both from direct observation of children, and in a broad way from a large body of research on childhood perceptual and motor development, notably by Britta Holle and several other Scandinavian researchers (9). Through detailed observation and research, Marcher and her colleagues linked specific movements to specific muscles.

Marcher et al also investigated the nature of each muscle’s “psychological content”. This was accomplished by palpating or otherwise activating a specific muscle and observing which psychological issues arose. Alternatively, they observed which muscles became activated when clients talked about specific issues. Numbers of people were tested to see if the issues connected to each muscle proved to be universal. In the formation of the theory over 10,000 sessions were analyzed through the reports of both client and therapist. This research correlated the muscle to the issue and age level evoked. It also related the elasticity or responsiveness of the muscle with patterns of resource, resignation. and holding on to old behavior.

As an example of what this research entailed, we will discuss one particular intervention. In an appropriate and relevant clinical situation, a client may be asked to push with their arm against resistance given to their hand (use of the triceps muscle). When a large number of people push in this way and are asked to describe their experience, many will speak about issues of how close or far away they want people, of how secure they feel in protecting themselves, and of what they don’t and do want. While each person’s individual experience is unique, there is a commonality in the theme. The themes here relate to having boundaries and saying “STOP”, or “NO”. The action of pushing, with its use of the triceps muscle, elicits and elucidates the nature of each client’s subjective (and historical) experience of saying “NO”, and what this brings forth for them.

II. MUSCLE RESPONSE AND FUNCTION

A central hypothesis in Bodynamic Analysis concerns the time period in which individual muscles come under voluntary control. There is observed to be a critical time period in which they acquire an imprint. This imprint is not simply about physical strength or kinesthetic ability. It concerns the psychological content or issue associated with the activity or function of this muscle. Thus the muscle encodes or “remembers” what happened in the emotional/ psychological environment in the time period in which it came under conscious control. A brief history of the development of the concept of muscle responsiveness is given in Appendix 1.

Building Resources

At the time when a muscle is first coming under conscious control, and is being used in its psychomotor function, a child is very responsive to the way the environment receives and responds to this particular action. A number of different imprints are possible, depending upon the child’s experience of responses to its actions and its need to be connected. It is our conclusion that as a muscle comes under conscious control developmentally, a neutral responsiveness will develop when its expressive use by the child is met with enough appropriate acceptance. This flexible, resilient, “ideal” muscle is one whose impulse is readily sensed, and whose motion is easily mobilized under appropriate circumstances. Equally, the muscle is relaxed when it is not required or is not functional. There is a choice to respond or not, to act or not act, as the situation dictates. In the language of Bodynamic Analysis, we call this a muscle that has resource. The psychological ego function that it enacts is integrated into consciousness. For example, when the postural muscles in the legs are resourced, the subjective feeling is of being able to stand on one’s own. Concurrently, the impulses and issues related to these muscles are easily available to conscious thought, as opposed to being either pre-conscious or unconscious. In physical terms we describe this muscle as having a neutral elasticity, or a neutral responsiveness.

It is important to distinguish between responsivity and tone. The tone of a muscle is conditioned through use, through life style or exercise. A muscle may be well toned or strong, but still be hypo-responsive and resigned in it’s psychological function. While we often recommend exercise to clients as a way to build body awareness and anchor new resources, exercise alone does not change responsiveness, it only changes muscle tone. To produce a lasting change in responsiveness, and a lasting behavioral change, the experience of using the muscle must be linked with verbal sharing and a conscious understanding of the related issues.

Hypo-responsiveness

If a child is repeatedly or severely frustrated early in the time period when a particular psychomotor action is coming under voluntary control, the muscle can become weakened in its responsiveness. This weakened response can also be created when the child has been confronted with an overwhelming task or was taxed too early in this aspect of development, before having the strength and solidity to tolerate this particular stress. We call this tendency the hypo-response. As an adult, the person literally does not sense much impulse in the muscle and therefore the psychological function is not so available. Use of this muscle will be accompanied by varying degrees of resignation, slowness, or loss of impulse. When a hypo-responsive muscle is activated the person may feel tired, the movement may feel too difficult or painful, and he may be easily distracted or want to give up. At times despair, sadness, and helplessness might arise. These feelings mirror those that took place during the time of the muscle’s imprinting.

Hyper-responsiveness

If a child is not frustrated early or severely, but only somewhat later in the imprinting time period, then he will have already mastered some of the physical and psychological abilities related to this muscle and its action. Now, in varying degrees he has to hold back, rigidify, or fight for his right to express himself. A different imprint will be developed, one we call a hyper-response. This hyper-response is actually what people are broadly referring to when they speak about body armor, a concept originated by Reich and recognized by most contemporary psychotherapists. In the adult the impulse in the hyper- muscle will tend to be restrained or strongly held back, or may be compulsively and repetitively activated. When a hyper-responsive muscle is activated a person may feel varying degrees of control, hardness, intensity, rigidity, and/or an overdoing. With high degrees of over control, a person feels cut off from others and from their own energy, and lacks flexibility and resiliency. He loses his resourcefulness. Interestingly, in a stressful culture such as ours, some degree of hyper-responsiveness in certain postural and boundary muscles is usually needed to be able to tolerate the stresses of the world. A person without these is vulnerable to being overwhelmed.

Fascia and tendon

The experience of Bodynamic Analysts is that psychological imprinting also applies to other tissues in the body. We believe that most if not all soft tissue may have a neutral, hypo-, or hyper-responsive dynamic. In particular, we also record certain fascia and tendon responses on the Bodymap. The fascia is a system of fibers that surround nearly all the soft tissues of the body (organs, muscles, etc.), serving to wrap, hold together, link up, and support these structures. We test fascia the same way we test muscle, though the location will be different. Often we have to distinguish between fascia and muscle tissue as they are intertwined. Psychologically speaking, fascia is a more primitive, less differentiated structure than is voluntary musculature, and it functions more along with the reflex system than the voluntary system. Thus it is more dominant very early in life, before the voluntary has had a chance to take hold, and it is also more involved in shock trauma situations where again, the voluntary has been overwhelmed by the involuntary. For example, we examine fascia points to detect the presence of unresolved birth issues.

III. THE BODYMAP

While exploring this newly delineated wealth of historical developmental information held in the body, Marcher and her colleagues struggled for a long time with the question of how they could make it more accessible to themselves, and ultimately available to other clinicians. Equally, they wanted to find the most effective way to use their knowledge to help clients. They needed both a format for presenting the muscle responsiveness information, and a framework, a psychotherapy system that would potentiate their findings, their knowledge, and their abilities.

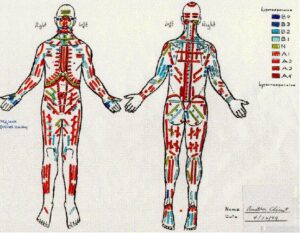

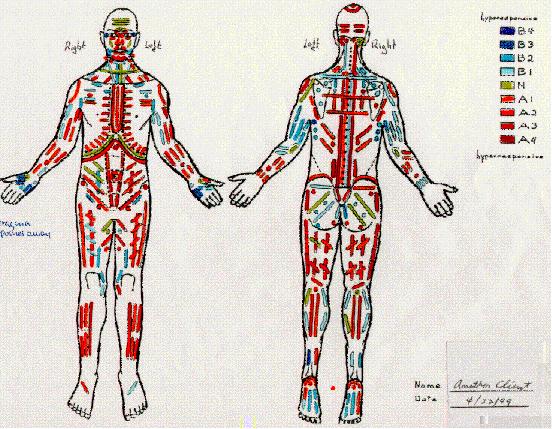

The solution to the question of a suitable format was the Bodymap. (“Danish” for body map!). The Bodymap is a mapping made for each client. It is a visual representation of each muscle’s responsiveness or elasticity. As shown in Appendix 2, Figure 2 A BODYMAP, each mark represents a particular muscle or part of a muscle. Each muscle response is recorded on the Bodymap form, which is an outline of a human body. Differences in responsiveness are recorded as different colors (see below). Several ligaments and fascial points are also mapped.

How a map is made.

The Bodymapping process is done with the client laying on a mat, fully clothed. The mapping takes between 3 and 4 hours, on average. The responsiveness of each muscle is measured by palpating it in a particular way . Each muscle is tested while it is in a relaxed state. Some muscles are tested in more than one place, and a few are tested at both a superficial and profound depth. This is done whenever different parts of the particular muscle come under voluntary control at different ages (e.g. triceps), or when the muscle has several functions. For example, all muscles that pass over more than one joint are tested in more than one place.

To measure the responsiveness of a muscle, the therapist first pushes into the muscle to a certain depth. Then, staying at this depth, he moves across or along the muscle fibers, stretching them. The responsiveness of the muscle is gauged as the tester withdraws across or along the fibers, relaxing the stretch while still staying at the same depth. The tester senses how rapidly or slowly the muscle returns after it has been stretched and is being released. If the muscle lags behind or returns more slowly than it is being released, it is hypo-responsive to some degree. If the muscle pushes or wants to return faster than it is being released, then it is hyper-responsive. If it returns at the same rate as it is released, then it is said to have a neutral response, denoting resource or flexibility.

On the first stretch of a muscle the tester usually determines whether the muscle is pushing his fingers back as he releases the stretch, indicating a neutral to hyper-responsivity; or whether the muscle is lagging behind the release, indicating a neutral to hypo-responsivity. On the second stretch the tester can focus on the degree of hyper- or hypo-responsiveness. Additional information is obtained from other properties of the muscle. Muscles that have higher degrees of hyper-responsiveness are limited in the amount they can be stretched, and this can be sensed. Muscles that have higher degrees of hypo-responsiveness do not fully follow the testers fingers all the way back to the point from which the stretching started. This can be both sensed and seen.

How the responsiveness is depicted.

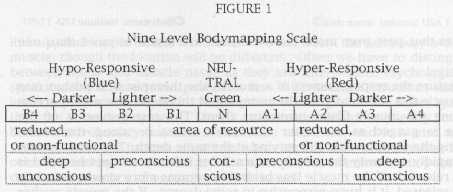

Through continued research it was found that one could repeatedly and reproducibly distinguish four degrees of both hypo- and hyper-responsiveness, and one degree of neutral responsiveness. To display this visually different degrees of responsiveness are represented by different colors. Muscles having a neutral response are colored green on the map. Increasing levels of hyper-responsiveness (named A1 –> A4) are represented by deeper shades of the color red. Increasing levels of hypo-responsiveness ( named B1 –> B4) are represented by deeper shades of the color blue . This is outlined in Figure 1.

The resulting Bodymap solved the problem of how to represent the wealth of information in a usable form. To the trained eye the densely packed information can be retrieved quickly. The Bodymap was also shown to be reproducible with 95% accuracy between different map makers (10). The specificity of the Bodymap grew over time into its present form, which continues to be refined to this day (Often to the dismay of students!). Several ways in which the data are analyzed are presented below. These are a partial answer to the quest for a suitable framework that could best put this new psychological information to use.

IV. ANALYSIS OF A BODYMAP

A history of the evolution of the framework of Bodynamic Analysis

Before the development of the concept of responsiveness, Marcher had initially worked with the concept of breaking down armor. Problems with this approach led her to seek out new methods and eventually a concept of hypo-responsiveness (Appendix 1). The new ideas led her to feel she had solved the problem that came from an approach that only worked with breaking down armor. She shifted away from talking about breaking down or getting rid of a defense system, the common approach at that time. Now she saw that the defense system was an appropriate response to a difficult historical experience, and that while it might be an inappropriate way of behaving in many contemporary situations, it was not negative in itself. She began to focus more on the rigidity of the defense system, the fact that a client seemed compelled to face certain situations in only one way. She saw that if the rigidity could soften, the client would have more possibilities for responding to the environment. Essentially, as a client became more conscious of their defense system they could recognize when they were going into it. They then became able to choose to go in or not. When you are able to make a choice, the defense has become more like a resource. Thus it is the ability to decide about one’s behavior that could make the behavior a resource and not a limitation.

As knowledge of the muscle functions grew, Marcher began searching for a system to organize all this information. The first organizing system was simply chronological. The muscles were broken down into all those that were activated inside of consecutive three-month periods. This system was quite unwieldy. It had too many boxes (time periods) and these were not easy to relate to adult behavior. Marcher examined Reich’s and Lowen’s ideas of character structure that also organized information historically. While these were more related to behavior, they had some of the limitations discussed above.

Marcher chose instead to look at the major developmental themes for each stage. She began to see how the psychomotor function of the muscles came into play in relation to the specific theme and developmental tasks for each stage. She was inspired by the work of Frank Lake who wrote at length about the classical “schizoid” and “hysteric” character structures (11). Lake showed that these greatly differently appearing structures arose from different responses to events in one and the same developmental time period. Marcher recognized that these two structures corresponded to an overall hypo- and hyper-response, respectively, to events encountered in that time period. She generalized this dual possibility of response to all character structures. And, additionally and quite importantly, she realized that there could be a good enough experience at any developmental stage, leading to a third possibility: a healthy or resourced position for that stage. This addition was influenced by the educational system in Denmark that was describing healthy development and functioning. With a model of healthy development teachers could look for what was not there, what learning had not happened, and help children to get what was missing. Marcher applied this to therapeutic work with adults.

How a muscle’s response changes from life situations.

Our experience has shown that the Bodymap reflects a combination of a person’s historical development and what is currently happening in a person’s life, emotionally, cognitively, socially, and psychologically. If a person who had never done any therapy was mapped periodically over many years, we would expect his map to have some changes, probably small, reflecting their changed life situation. Life’s stresses are different, people have come and gone in his life, he has entered into different life phase issues, etc. Character patterns seen in the map are relatively stable over time and tend not to change significantly (at least for the better) without therapy or other significant efforts at personal growth. Sometimes we will see a situation where a person’s character stance is strengthened in a negative way when he is hit hard by a loss or a shock, or a life situation of some kind. He may become more rigid or resigned, or both.

We often speak of the teenage and young adult years as the time when the final set to our character takes place. If life treats us reasonably well during these years, we may soften our stance toward life and be able to focus our energies on positive life goals. If however, life is hard, a person may become more locked into his structural stance toward the world. An historical review of these stressful years can often be correlated with “darker” muscles on a map.

Character Structure and the Bodymap

Character structure is a term used in psychology to denote a person’s typical patterns of behavior, especially in stressful situations (1,2). These patterns are created when the environmental response to early behavior is less than adequate in an ongoing way. From a psychological perspective, at the heart of each character issue is an unconscious or preconscious decision about who one will be in the face of the world as experienced at the time the character position is formed. E.G., “I’ll never cry again – people always laugh at me.” “I have to hold onto my opinion, or else I will lose my ability to think.”

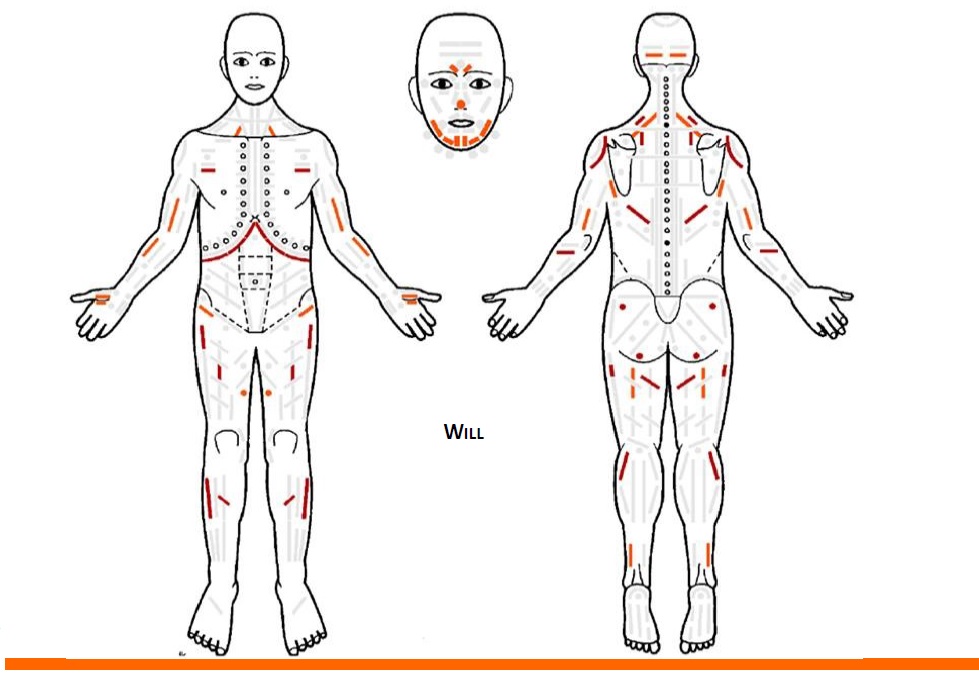

Different schools of psychotherapy have their own theories about what character is and what kind of “types” there are. Historically important contributions to characterology have been made by Freud, Reich, Lowen, Erikson, Boadella, Keleman, and others. The contribution made by Bodynamic Analysis is detailed in reference (3). In Bodynamic Analysis, character structure is also seen as those particular patterns that can result from attempts to deal with different developmental tasks or issues. While the idea of characterology comes from early psychoanalysis, the Bodymap makes the character levels more than just psychological descriptions. It makes them more concrete, and less metaphorical. From a somatic perspective, Bodynamic Analysis has correlated the sequential developmental stages with specific muscles and their associated psychomotor functions. Thus the pattern of hypo-, hyper-, and neutral responsiveness of the sub-group of muscles corresponding to a given developmental stage give us a literal depiction of that stage, and tell us a great deal about the characterological imprint from that stage (See Appendix 2, Fig. 3, for example).

An empirical knowledge of the psychomotor functions of the muscles in each stage has allowed us to define the stages more precisely, in terms of their developmental tasks and the associated motor activities. It has enabled us to distinguish the activities of one stage from another, especially when the stages overlap chronologically, and allows us to understand better how the lack of resources from an earlier stage affects the later stages. This empirical knowledge has led us to recognize and describe two later developmental stages not described by Reich or Lowen. While Freud and Erikson characterize the ages 5 to 12 years as the latency period, Bodynamic Analysis divides it into two periods with different developmental tasks.

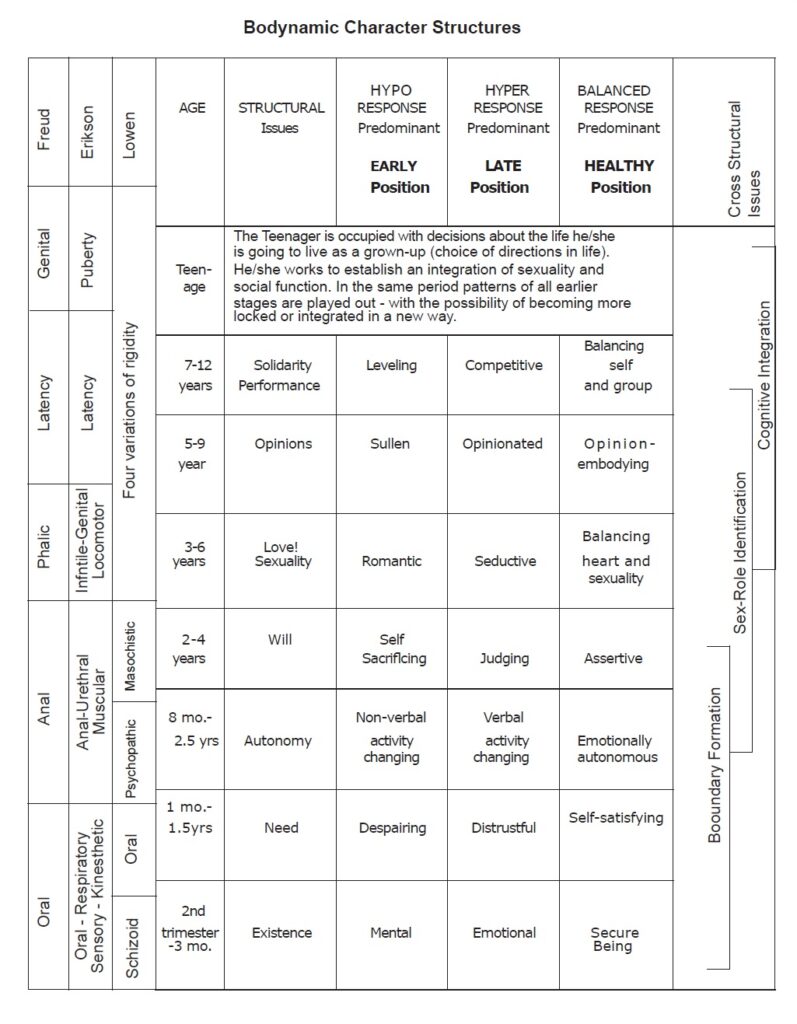

V. THE SEVEN DEVELOPMENTAL STAGES

After amassing a tremendous amount of information about motor development, and by observing the interaction between the psychological and emotional developmental processes, the Bodynamic system of character structure evolved into seven character stages or types. Each stage is based on a specific developmental theme and is named after that theme. The seven stages are:

- EXISTENCE (intrauterine period to 3 months postnatal.

- NEED (1 month to 18 months)

- AUTONOMY (8 months to 2 1/2 years)

- WILL (2-4 years)

- LOVE/SEXUALITY (3-6 years)

- OPINIONS (5-9 years)

- SOLIDARITY/PERFORMANCE (7-12 years)

These stages are depicted in Appendix 3. Each character structure has three possible “positions”. These positions to which of the three types of muscle responsiveness is most predominant for this character structure These are named the “early position”, the “late position”, and the “resourced position” (formerly called the healthy position). Looking at the subset of muscles that correspond to a given character structure (.e.g., Appendix 2, Fig. 3 depicts the Will Structure, 2-4 years of age), if we should see more hypo-responsive muscles, this indicates an early position for this structure, showing more resignation at that particular age/stage. In the late position we see more hyper-responsive muscles, indicating a struggle with control. In the resourced position, we see neutral and mostly the lightest hypo- and hyper-responsiveness. Typically people possess a mixture of positions, indicating different experiences and responses to the environment and to the tasks of the different ages. For example, a person’s Bodymap may be said to indicate an early existence position, a late need position, a resourced autonomy position, etc. Overall there are 21 possible positions, corresponding mathematically to over two thousand different combinations possible.

It is important to recognize character structure as only a description – a map and not the territory – and that each person is more complex than their patterns of muscle responsiveness. What the Bodymap can provide is deep insights about how a person functions. A typical Bodymap has significant amounts of all three types of muscle response: resource, hypo- and hyper-response. How these various responsivities interact, how different developmental levels and different layers of abilities express themselves, determines one’s unique character. With the Bodymap these patterns are revealed in very clear ways, ways new to psychotherapy. Thus we are able to be more precise and broad in our understanding. In fact the Bodymap has and is showing us new ways to think about character and personality. It helps us to form a container in which we explore and experience the unique resources, subjectivity, and needs of each client.

VI. THE TEN EGO FUNCTIONS

In addition to character structure, there are other broad concepts that are used by body psychotherapists to describe how clients function. These concepts include grounding (primarily developed by Lowen), centering, boundaries, contact abilities, etc. These concepts relate more directly to the body, and are often spoken of as attributes, e.g. “I tend to lose my grounding in some social situations”. Bodynamic Analysis addresses these concepts with its elaboration of ten “ego functions”. These ego functions extend the description of human functioning from a body oriented perspective. They also provide a second large framework that renders the muscle response information directly useful in psychotherapy. This framework addresses the body even more directly than does character structure. The ego functions themselves are comprised of related resources, and include abilities from many developmental stages. They are named for the themes and psychomotor abilities that they relate to: Connectedness, Stance in life, Centering, Boundaries, Grounding and Reality Testing, Social balances, Cognitive Skills, Energy management, Self Expression, and Interpersonal skills. The list of the ten ego functions and their components in Appendix 4 gives a sense of how they are used in interpreting a map.

The analysis of a Bodymap in terms of these ego functions opens a completely new possibility for psychotherapy. No longer are the functions simply metaphors for human abilities and potentials. Each ego function is comprised of a number of resources whose presence or absence in the body can now be measured. The Bodymap show us how much resource, hyper-, or hypo-response a person has in each area of ego functioning. It tells us how well we may expect a person to function in a particular area. For example, if a person is hypo-responsive in the muscles corresponding to the function of “standing up in the world” (a resource included in Positioning), then certain basic tasks in life may often be experienced as overwhelming. For example, he may have difficulty holding a job, or dealing with the everyday stresses of relationships. If on the other hand, this person is too hyper-responsive in these areas, he may handle stress well, but be locked into strategies that lack flexibility. He may be governed more by a narrow range of repetitive behavior, rather than being responsive to the situation at hand.

Every ego function has it’s own developmental timetable for unfolding. For example, an infant in the womb has little sense of a boundary or ability to defend it. As he matures, newer abilities in that function emerge. With each successive stage, he becomes increasingly capable of sensing and holding boundaries. From an analysis of a Bodymap in terms of ego functions we can trace the course of development of a particular ability, and pinpoint age levels where resources are developed or where there appear to have been problems. Typically, adults have good resources in some areas and have lacks or rigidities in others. The functional analysis of the map provides a thorough and multi-layered picture of a person’s abilities.

VII. BODYNAMIC ANALYSIS AND THE BODYMAP

The Bodymap can be used to help a person understand their present functioning in terms of their own history. The information it contains helps individuals understand how they might tend to respond under stress, in relationships, at work, and in achieving their own personal goals. The Bodymap can also be used to clarify people’s description of themselves. For example, take the statement “I don’t have friends”. The map might show that the person has the ability to draw people towards them. But it might also show that the person lacks the ability to push people away, and that friends can then become a great burden. The map can also give indications about specific issues that could be focused on to help get maximum benefit and growth from therapy.

We think of our work as a mirroring process that helps people sense what they do. We do not use a medical model of illness and cure, nor do we see therapy as simply a corrective experience. We assume that certain structures (character positions, ego functions, rigidities and resignations) have evolved with which the person may feel stuck. Usually, they have seldom had a clear experience of these structures. When appropriate we may try to hold someone in the experience of a structure until they can sense it in their body. In relation to us they can begin to feel this structure, this place they live with. As we work with them to promote a new and positive experience, the power of the habitual structure (or lack of structure) diminishes. An opening to new, possibly unknown options becomes available. New capabilities are developed and the person has more choices available in their life.

As discussed above, the empirical research done by Lisbeth Marcher and her colleagues at the Bodynamic Institute, Denmark has shown us that each muscle is connected to specific psychological issues. With the aid of this knowledge and a Bodymap, the Bodynamic Analyst can pinpoint muscles that are likely relevant to an issue being worked on. The Bodymap implicitly contains a prescription for therapy that says, “Bring these (darker) muscles towards resource”. We do this by working with the corresponding psychological issues, or by building related resources. Building these resources can often allow an issue to come more into consciousness. In general, we use the body to bring into awareness the person’s historical response to an issue we are currently working with. By stimulating the content of the muscle, either through specific, attuned touch, or by using the muscle in specific ways, we can help a client to sense their impulse, attitude, sensation, emotion, or even decisions related to this issue. They become able to understand a problem and their response to it differently. Since the core of an issue can often be addressed directly, a more rapid resolution and a fuller integration are frequently achieved.

When we believe a person is working with a particular character position or ego function, this will guide our interventions. When working with a client we find it important to ask ourselves what we are doing moment to moment. The process of exploration of structure is always one of trial and response. In one session, for example, three existence stage interpretations were responded to with love/sexuality material before it was recognized that the latter stage had risen to the surface. The client’s response tells us about the correctness or appropriateness of our analysis or choice of intervention. Are we truly listening, or only wanting to hear what our theory tells us is relevant? Are we too sure about what we are doing, and possibly missing new information?

Starting therapy

The Bodynamic Analytic approach to the start of therapy incorporates a number of elements. One is the Bodymap, analyzed in terms of character structure, ego functions, and the presence of indications of shock trauma. A second is the client’s report of his history. This will be pursued further if there are specific questions arising from the Bodymap. A third is the desires the client has for the outcome of therapy. A fourth is the therapists evaluation of the client’s resources, and his present level of functioning, stability, and support. These will be considered in formulating a contract that the therapist makes with the client. The contract makes explicit the goals of the therapy and the areas the therapist believes need to be explored to achieve these goals. Whenever possible, an estimate of the duration of therapy is made.

Building resources

Each person has a mixture of neutral, hyper- and hypo-responsive muscles corresponding to their own history. The map shows exactly at what age levels and in which ego functions a person has resources or is lacking them. The map can tell us, for example, whether a high-functioning person may have abilities from later developmental stages, but have missing resources, or “holes”, underneath, from earlier stages. This person may get security and respect from their accomplishments, yet have anxieties and feelings of depression that go unacknowledged and unrecognized. Having these feelings recognized and addressed by the therapist can be very affirming and relieving. In this situation resources missing from the earlier stages must be built up before the defenses from the later stages are confronted, and before regressive work with the earlier stages is attempted. Otherwise, the person may be thrown into an anxious or depressed state very different from what they are used to and how they envision themselves. This state will be lacking in resources and can be quite disruptive to their life and to the therapy.

Conversely, a person having a lot of day-to-day difficulties may be discovered to have early resources that can be built upon. In general the map can alert us see contradictions and congruences. This may lead us to question whether specific information is missing from our knowledge of a person’s history, or indeed, from their own knowledge.

A basic tenet of Bodynamic Analysis is that when people can awaken inner resources they will live fuller lives. In therapy this manifests as one of our basic principles: that working with areas of resource and flexible functioning will spontaneously begin to mobilize areas of decreased functioning. Thus, we usually work on relatively resourced areas first, corresponding to lighter colored muscles on the map (Fig.1). New and positive physical, cognitive, and emotional experience in the present can lead to a change in the responsiveness of related muscles towards more resource. Sometimes this change is immediate, and generally it becomes more permanent with repeated positive experiences that lead to a re-decision. This change in muscle responsiveness is quite different from only having a new cognitive awareness about an issue. In the latter case, when the related issue arises a person goes through a process of realizing that he does want to act in the old way, and deciding again to act in the new way. When a new imprint is established in a muscle, the person will not only have a new cognitive awareness about the issue, but will also reflexively respond to this issue in the new way.

Working with hypo-responsive muscles: Waking the impulse.

Recognizing patterns of resignation, as shown by the hypo-response in muscles, provides us with a very powerful tool for understanding people’s behavior. When we are in a state of resignation or hypo-response, the danger is that we cannot sense our impulses. Over time we may come to recognize the fact of not having certain impulses, and to feel the pain of that, but we may not sense the impulse itself. In the deepest resignation, we lose even the pain of not having an impulse, and all traces of the impulse become unconscious. Resources are absent and we are in a state of forgetting. In its extreme, each defense has great existential costs, but the hypo-response often places stronger limitations on behavior and makes being in an inherently stressful world more difficult.

In working therapeutically with the hypo-response we are often teaching and sometimes in the role of a teacher. The corresponding missing ability was either never learned, was given up, or is not sufficiently sensed or trusted. The therapist provides understanding, support, contact, relevant information, and contextual insight in helping the person towards a newer, affirmative, appropriate experience of the issue being worked on. Somatically, through support, words, gentle touch, or gentle movements, the task is slowly to reawaken the impulse in the muscle. The more hypo the muscle, the more gently it should be awakened. The same is true at the psychological level. In response, the person often may feel “I can’t”; “I don’t want to do it; It’s too hard; It’s too scary”; etc. In a supportive way we may first help a person to sense or move their body until they feel an impulse related to this issue. While hypo-responsiveness is a kind of defense, since issues tends to disappear from consciousness, there is less resource in this defense than in the hyper-responsive defense. To confront a hypo-response can bring a feeling of being overwhelmed, or a sense of being asked to do something you can’t do. Strong confrontation of people with significant hypo-responsiveness can lead to feelings of disintegration, fragmentation, or mistrust.

Working with hyper-responsive muscles: Challenging the defense.

Patterns of hyper-responsiveness present a different challenge. The hyper-responsive muscle over-controls and holds back the impulse it contains. With related issues the person had to learn to hold back and to control. There is a sense of holding back, of pushing, and/or of control of energy. He may fear that if he lets go something terrible will happen: e.g., that he will be attacked, or he will lose his ego control. He desires to be met in his intensity, yet fears being overwhelmed. In working with hyper-responsive muscles, one goes up to the boundary and metaphorically, solidly but respectfully knocks at the door, signaling: “Hey you in there: I’m here, I see you, and I can handle what you’ve got. Come on out. I insist.”. We may help the person to stay in the experience of the structure without any distraction, movement, conflict, or interaction that might take them out of the experience. If they leave the experience, we help them to keep returning. Whenever possible, we attempt to stay with one issue, preferably at one age level, until it is resolved. In our experience, this greatly increases the probability that the resolution of the issue will be integrated in both body and mind.

When working with issues corresponding to hyper-tonic muscles we can be more confrontive because there is enough energy present to handle this. In fact, this is often what a person needs in order to sense himself. The therapeutic task is to release the energy in the defense in a way that is not experienced as dangerous, and to balance this with the fact that addressing these issues too lightly may not be of much help.

Re-testing

After major life changes have occurred during a course of Bodynamic Analysis, or for research purposes, we may partially or fully re-map a person to see what responsivity changes have occurred. Most often the new map is lighter, with lighter degrees of hyper- and hypo-responsiveness. Sometimes, for people who have tended to be more hypo- overall, many of their muscles will have moved toward light hyper-. They have gained more defense and more structure. This often shows up in their life as being better able to tolerate stress at work, more intensity in relationships, etc. At times, however, muscles are seen to be even less functional, having become more hyper- or hypo-responsive. Or they may even move from hyper to hypo or the reverse. At first this was surprising to the original Bodynamic researchers who developed the map. But since it happened often, they came to understand it as an indication that there are layers to the defense system that emerge in different contexts. When a person who has a strong, early defense system (early existence, for example) starts to have more emotion and body sensation, starts to feel more alive, he may first begin to sense the need for more defenses. Thus some muscles may become darker, usually for a temporary period. This can be seen on the map and discussed with the client.

A new map or a partial map of selected muscles, can also help us by indicating what is or is not working in therapy, and how we might need to re-focus the work.

- Are we not taking into account certain elements of a person’s structure?

- Are there other aspects of the self that need attention?

A new map also provides an objective tool for assessing a person’s progress in therapy. In this way it complements the therapist’s and client’s sense of the progress that has taken place.

VIII. A SESSION – USING THE MAP

A session with Carey: His truth came through pushing.

Carey, a male in his mid-forties, came to session wanting to be more assertive in general, and in particular work with how he continually gives in to his ex-wife’s demands; how he sacrifices his own feelings, knowledge, and desires. When they met and married, 20 years before, her education level was far below his. He had taken it as his task to help her become educated and find fulfilling work. It seemed however, that she would be very satisfied if he just took care of her financially. At a surface level it was true that he was hardly able to say “NO” to her. At a deeper level he understood that he was treating her similarly to how he relates to his mother. As we talked, I (J. I.) remembered from his Bodymap that his triceps muscles were hypo-responsive. I proposed that he use these muscles to push against my resistance, while exploring different verbal expressions meant to be addressed to his ex-wife. The instructions were to “see what happens when you try this”. I wanted to explore whether his appreciation of the issue, his understanding, and abilities changed as we worked with this resource.

At first he pushed and said it felt mechanical. Then, as I asked him also to focus on his center, the experience of pushing became more involving, more meaningful for him. As associations or historical material came up, we would explore these briefly. The more he connected with his center and his grounding, the more the pushing helped him to recognize whether or not the phrases he was addressing to his ex-wife were appropriate. As we progressed, I realized I was beginning to understand his subjective experience of assertion. This was allowing me to attune my verbal interventions and my suggestions for his attention to and use of his body. It became apparent that we were performing an experiment to explore his understanding of himself, the issue of assertion, his relationship with his ex-wife, his relationship to his mother, and more.

As we continued he was visibly discovering his truth. He could feel it in his body. From the trend of what he was expressing I suggested, as a next step, that he experiment with the phrase “I can’t change her”. This brought him to resolution. It was an essential understanding for him; and it arose from the pushing. He recognized that he could immediately begin to act differently towards his ex-wife. Along with being excited, Carey was very curious, even disconcerted, that his previous therapies had not come led him to this connection and understanding.

The primary ego function worked with there was Interpersonal Skills (See Appendix 4, #10) , and the sub category was “Pushing Away (saying “NO”) and “holding at a distance”. The corresponding muscles, most importantly the triceps, were all slightly hypo-responsive. The therapy process deepened when the ego functions of Centering (#3), and Grounding (#5), were brought into awareness. Another layer of the problem can be approached through working with Boundaries (#4), and specifically the sub category Self-Assertion. This latter category involves three parts of the deltoid muscle, all of which are more strongly hypo-responsive for Carey. From a characterological perspective many of the muscles involved here are related to the Autonomy and Will stages. The themes of these stages concern being independent, having your own feelings, being powerful in your actions, etc., while still being loved and cared for.

While we started with an exercise involving a resource that might help Carey to be more assertive, by exploring somatic responses we arrived at an important motivation behind his non-assertive behavior. His present behavior was now on the way to changing without having had to explore his childhood in detail. The specificity possible in Bodynamic Analysis helped Carey to get to a core issue quickly. Investigating the possible origins of his present behavior in his relationship with his mother, while it would be interesting and potentially helpful, was not necessary here. Additionally, it is our experience that the resources a person develops while working with a contemporary situation will generally shorten and simplify any historical work with the related issues.

IX. AN ANALOGY

We can make a useful analogy between muscle responsiveness and playing a piano. Imagine each key on the piano to be like our individual muscles. We can think of character structure as a musical style that only uses a small range of the piano’s capacity. Because of patterns of tension we can’t play some keys, we hit others only occasionally, play others too hard, and still others weakly. Our full expression is limited by not having access to all the possibilities. The more limited the character by tensions and resignations, the more limited the range in the style.

As more muscles move towards resource and the psychological abilities become more available in consciousness, our emotional range becomes broader. We can express ourselves in more subtle and varied ways. By unlocking our resources, our potential, we move into new realms of possibility, of utilizing our full abilities.

Continuing with the piano metaphor, we can see that just as single notes can combine to form cords, harmonies, and melodies, so can our new muscular freedom and responsiveness lead to new types of movements and expressions. The therapy process is analogous to helping an improviser on the piano begin to venture out and bring new elements into her playing. First, perhaps, staying within her original style by adding small variations, and then on to broader and broader explorations into the world (of music).

Sometimes, watching a Bodynamic practitioner probing different muscles is also like watching a musician: playing softly here, loudly there; trying first one tone then another; getting the most from the instrument (client) and the most from the music (issue) by balancing each element toward an integrated expression.

One implication of Bodynamic Analysis is that each of us can approach our life like an accomplished musician with full command of our instrument. We can shift our consciousness, our capacity to relate, to work, and to play, by intentionally sensing and using our body. For example the person in business can learn to manage stress in meetings by tensing particular muscles; the person who gets stuck in depression can begin to wake certain impulses, etc. So, No matter which “key or tone”, “style or expression” a person starts with, one of the goals of Bodynamic Analysis is to help him be more in flow with his own possibilities, to perform at a high level while maintaining and enhancing mutual connection.

In mutual connection one is in contact with oneself and with the other person. When a person acts primarily from an early position of a character structure he has a tendency to collapse, to give up getting contact, or else to give up himself. A person acting from a later position will tend to go into a fight to be able to keep the contact or the connection with himself. In fighting, however, he doesn’t really get either, or he may be unable to sense when he gets either. A person in the early position must learn to fight for connection, and in the late must learn not to fight. From this perspective we can say that one of our “goals” is to have a client write his own music and be able to perform it for others.

The Bodymap, while requiring a knowledge of anatomy and muscle function, and requiring some effort to make and analyze, greatly clarifies, simplifies, and guides our work with clients. In this sense it may be likened to a musical conductor.

copyright ©1997 by Bodynamic Institute USA

REFERENCES

- Reich, Wilhelm Character Analysis, 1933. See 3rd Edition, Touchstone, 1972

- Lowen, Alexander The Language of the Body, Collier Books, 1958, and Bioenergetics, Penguin Books, 1975.

- Peter Bernhardt, Marianne Bentzen, and Joel Isaacs; Waking the Body Ego, Part 1 and Part 2, in Energy and Character Vol. 26, #1; Vol. 27 #1; Vol. 27 #2.

- Ian Macnaughton, (Editor), (1997) Embodying the Mind and Minding the Body. Integral Press, N. Vancouver, BC.

- Stern, Daniel The Interpersonal World of the Infant, Basic Books, 1985.

- Maslow, Abraham

- Marcher, Lisbeth See, for example: Bernhardt, P. (1992) Individuation, Mutual Connection, and the Body’s resources; Pre- and Peri-Natal Psychology Journal 6(4), 1992.

- Britta Holle (1976) Motor Development in Children: Normal and Retarded. Blackwell Scientific Publication, Oxford.

- Ollars, Lennart Muskelpalpationstests palidelighed, Thesis, University of Copenhagen, 1980. (Reliability of the Bodymap Test – in Danish) Available from Bodynamic Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Lake, Frank Clinical Theology (no longer in print).

- Johnsen, Lillemor See for example: (1981) Integrated Respiration Therapy.

- Braatoy, Trygve

APPENDIX 1.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE CONCEPT OF MUSCLE RESPONSIVENESS.

As was the practice at the time, Marcher worked primarily with breaking down a client’s armor, their hyper-tonicity. However, she was disturbed because this led to some clients experiencing psychosis, especially (in retrospect) if they had experienced PTSD in their life. A possible alternative to only working with armor was revealed to her in reading articles by Lillemor Johnsen, a Norwegian physiotherapist. Johnsen essentially gave a description of hypotonicity, and worked with this so patients began to regain the life impulse (12). At the same time another Norwegian, Braatoy was describing his work with clients (13). Marcher realized that he must essentially also be working with the hypotonicity.

In 1969 Macher arranged for Lillemor Johnsen to come to Denmark to teach. Johnsen demonstrated how she worked with areas of the body and how she “listened to muscles’; how she touched a client, and how she watched the client’s breathing response. While skilled at what she did, it turned out that she could not describe precisely where she chose to touch, nor precisely describe what she did with her touch. This made it difficult to learn from her. She did work in some way with the elasticity of the muscles and the effect of touch on the breathing response. In hindsight we would also say that she worked with patients who had strong early disturbances (prenatal or first year of life).

Lisbeth Marcher set a goal for herself to find a way to work with the hypotonicity that she could describe to others, that she could teach. She also realized that the word “tonicity”, which Johnsen and others used, was not a good choice to describe this new work. At the time it had a different and very specific meaning in physiotherapy. Instead, the word “response”, was chosen. Marcher worked with muscles for one-half year until she could recognize basic patterns of hyper- and hypo-response. She was also able to sense varying degrees of responsiveness. As she worked with the hypo-responsiveness more impulse for life came into the therapy. Marcher realized that working with lighter degrees of responsiveness was important with less disturbed people. She soon set about teaching all of this to others around her.

As the work developed it became more and more specific. While Johnsen had mapped areas of the body, Marcher began to test and map specific muscles and parts of muscles. Long term empirical studies were undertaken on the links among the phsiological, the motoric, and the psychological. Specific muscles and their physical function were correlated to both their associated psychological function, and to the time period in which they came under voluntary control. Over time, the specificity grew and developed into the present form of the Bodymap, which continues to be refined to this day.

APPENDIX 2.

Figure 2. A BODYMAP

Each line indicates a muscle or a part of a muscle that is tested for its responsiveness and marked in its corresponding color (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 3 THE WILL STRUCTURE

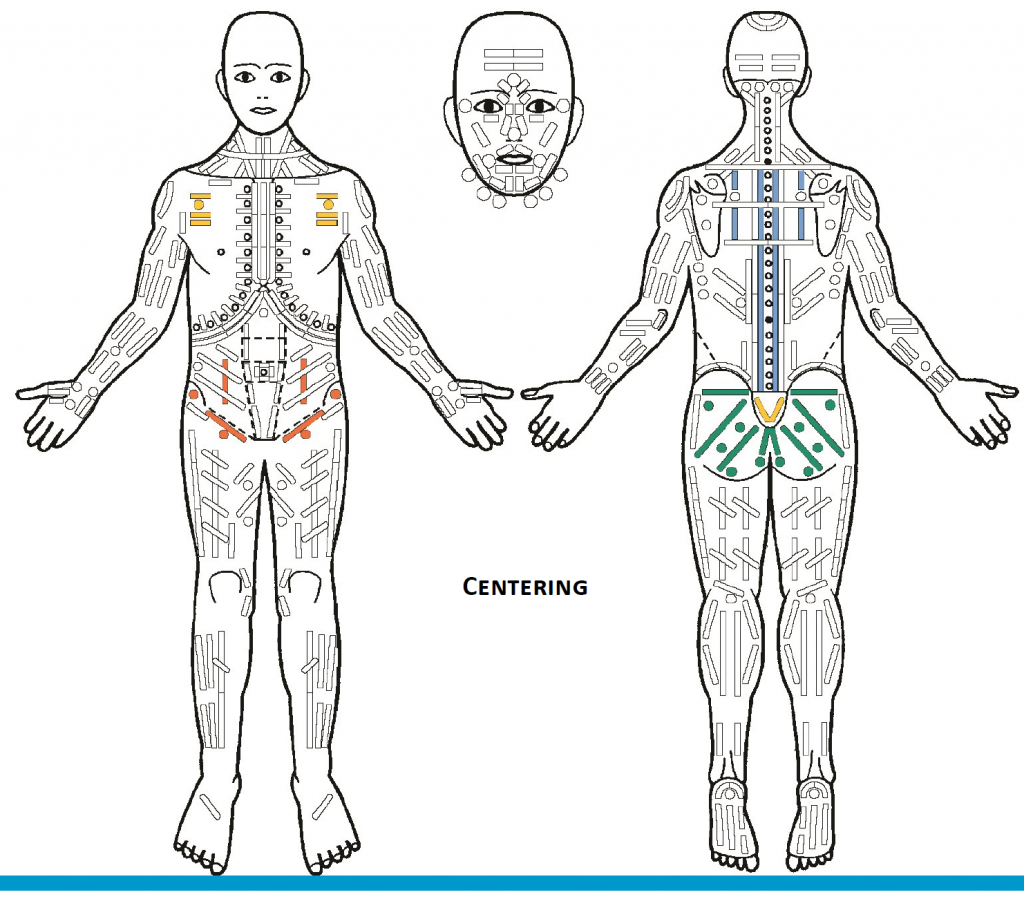

Fig. 4 THE EGO FUNCTION “CENTERING”

APPENDIX 3. THE BODYNAMIC CHARACTER STRUCTURES

APPENDIX 4. THE TEN EGO FUNCTIONS

1. CONNECTEDNESS: Taking in; bonding; opening the heart; accepting support, feeling “backed up”; bonding; heart contact/opening .

2. STANCE IN LIFE: (“POSITIONING”) Existential position; stance towards life; poise for action. personal stance; standing on one’s own; position on values and norms; orienting (keeping or loosing one’s head).

3. CENTERING: Filling out (from the inside); being oneself in one’s different roles; feelings of self worth.

4. BOUNDARIES: Boundaries of personal space (energetic boundaries); self assertion(making space for oneself in social contact).

5. GROUNDING AND REALITY TESTING: Ability to stand one’s ground, feel rooted and supported by it; relationship to reality; relationship to spirituality.

6. SOCIAL BALANCES: Balancing one’s own needs/feelings/desires against others’ expectations; balance of pulling oneself together/letting go; balance of facade versus openness in interactions; balancing being oneself with being a group member; balance of managing stress and resolving it.

7. COGNITIVE SKILLS: (“THINKING”) Orienting cognitive grasp; understanding (getting something well enough to stand forth with it); grasp of reality; ability to apply cognitive understanding to different situations; planning; contemplation/consideration.

8. ENERGY MANAGEMENT: Building charge, containment and discharge; emotional management; stress management; self containment; perception and mastery of one’s own sensuality

9. SELF EXPRESSION: Assertion; asserting oneself in one’s roles; forward impetus and sense of direction.

10. INTERPERSONAL SKILLS: Patterns of closeness and distancing; reaching out, gripping and holding on; drawing towards oneself and holding close; receiving and giving from one’s core; pushing away (saying no) and holding at a distance; releasing, letting go.